Professor Tony Culyer

CURRICULUM

VITAE

Professor

Anthony John (Tony) Culyer, CBE, BA, Hon DEcon, Hon

FRCP, FRSA, FMedSci

|

|

Welcome to my Home

Page!

I hope that clicking on the appropriate topic below will get

you to where you want to be

If you have difficulty downloading anything, let me know and

Ill e-mail it to you

|

CV

CV

Current articles

Current articles

Journal

of Health Economics

Journal

of Health Economics

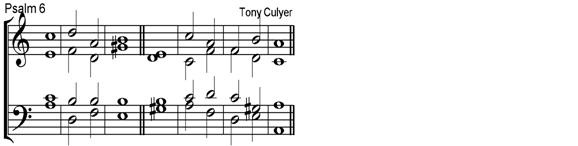

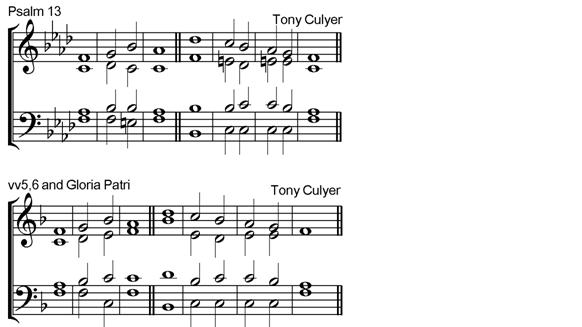

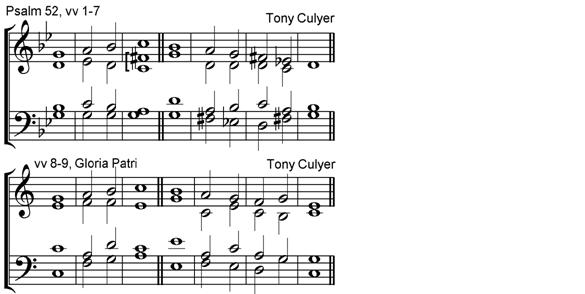

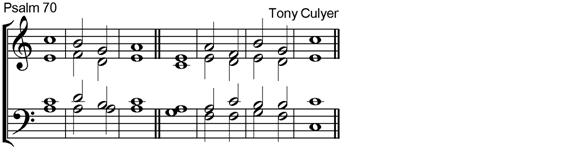

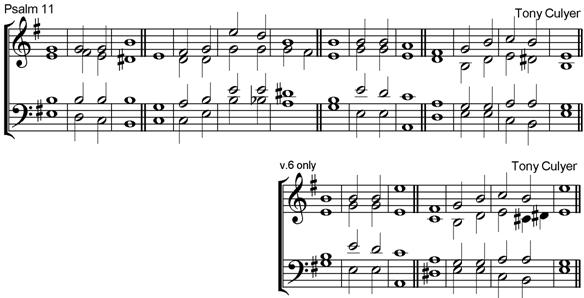

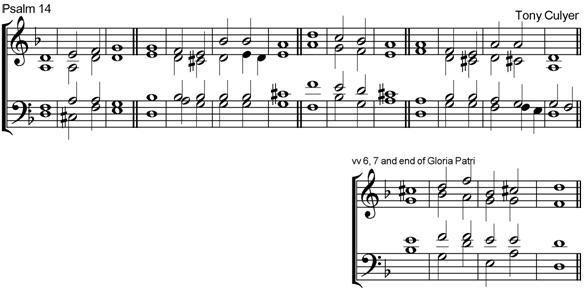

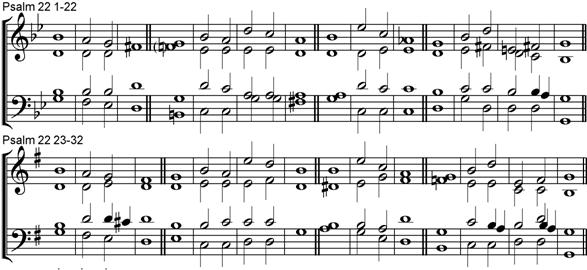

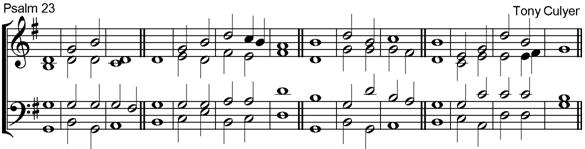

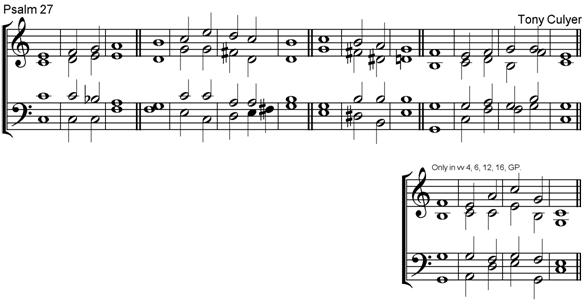

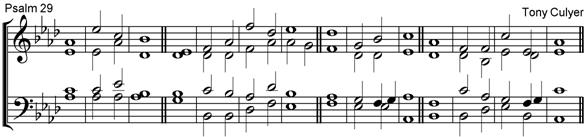

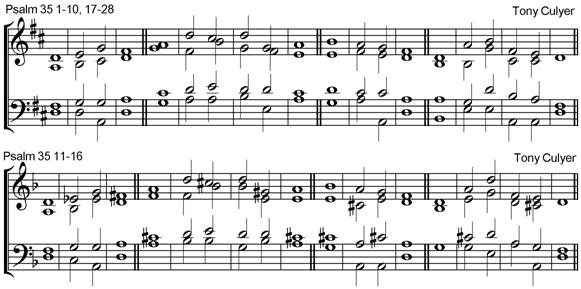

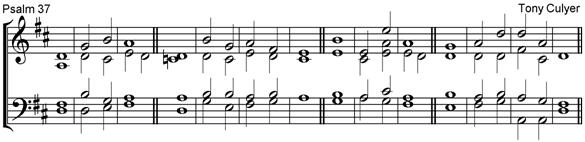

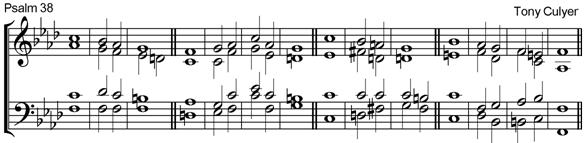

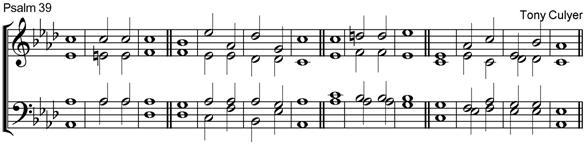

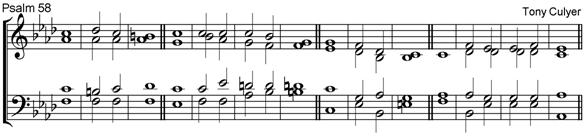

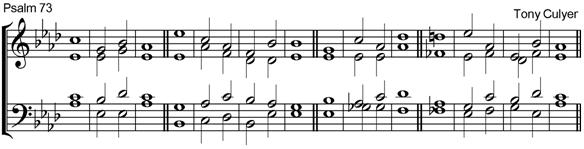

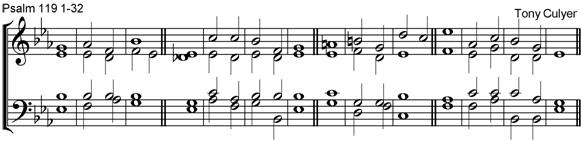

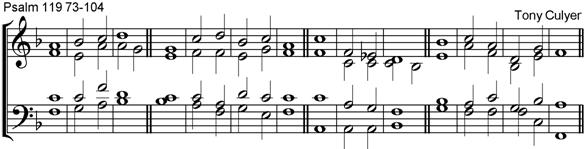

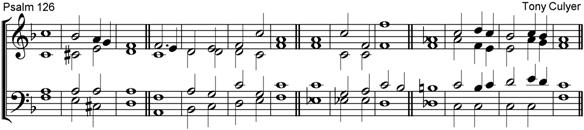

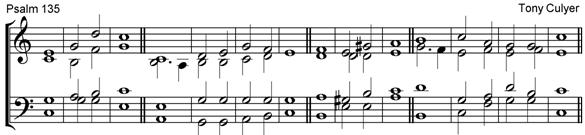

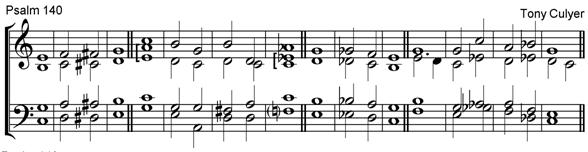

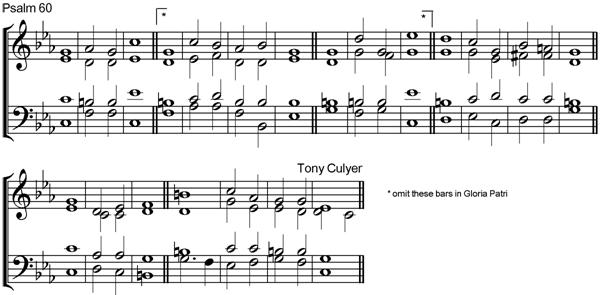

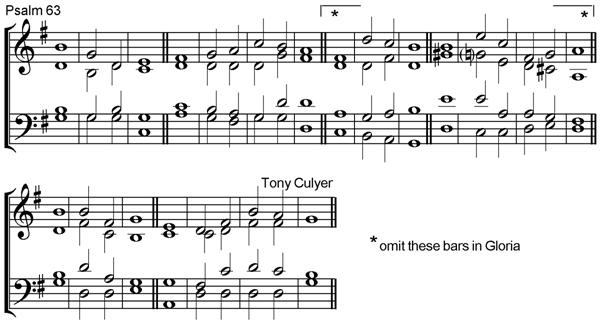

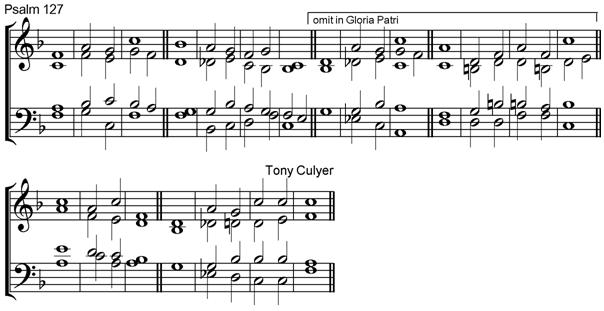

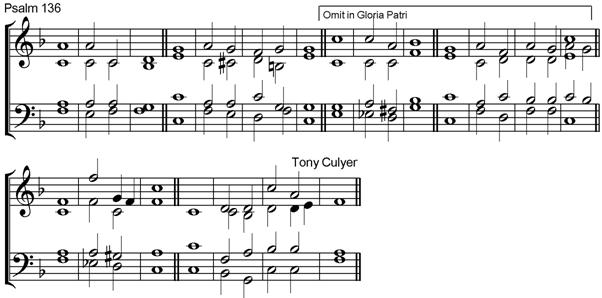

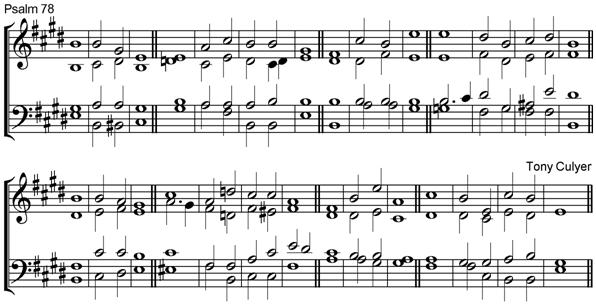

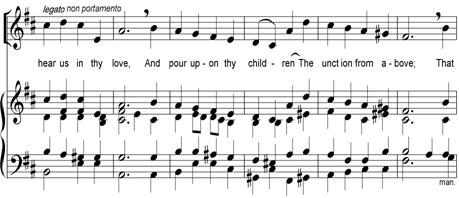

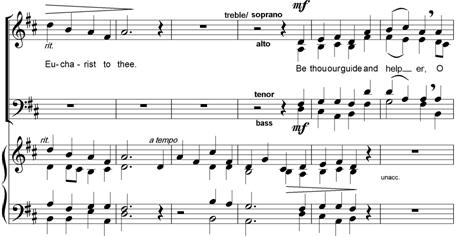

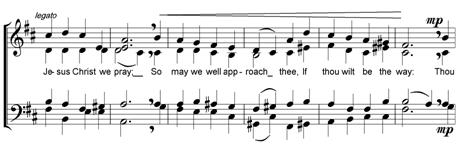

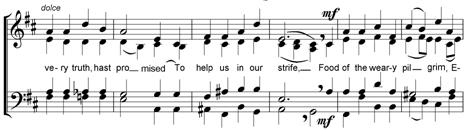

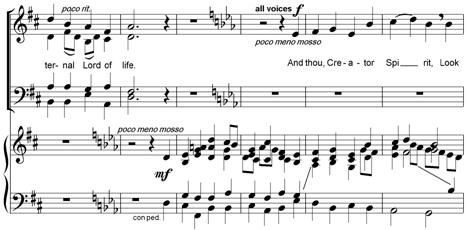

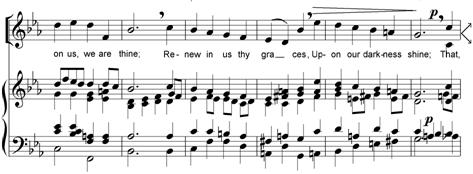

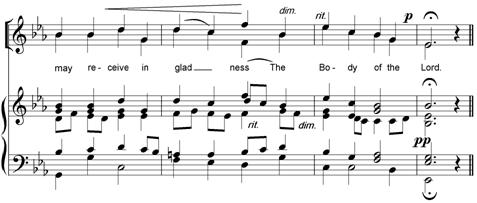

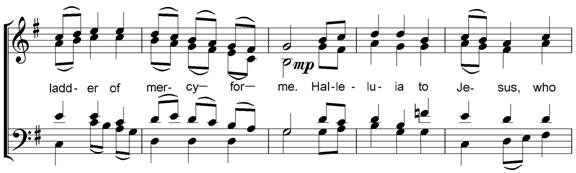

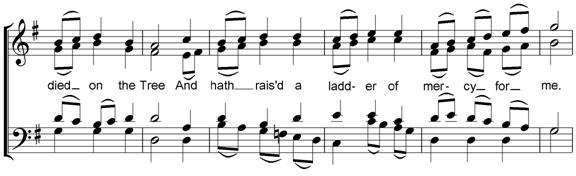

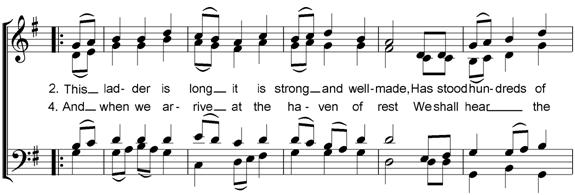

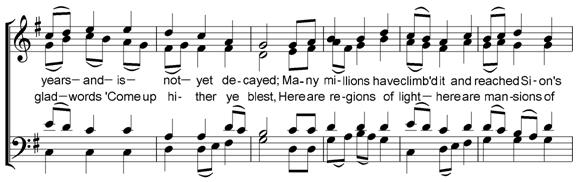

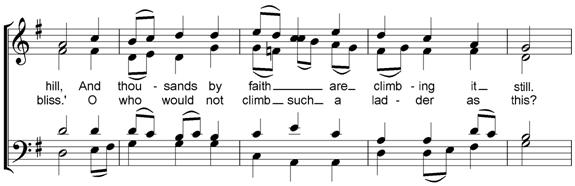

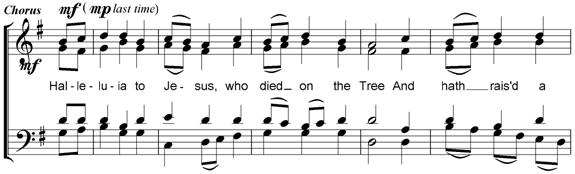

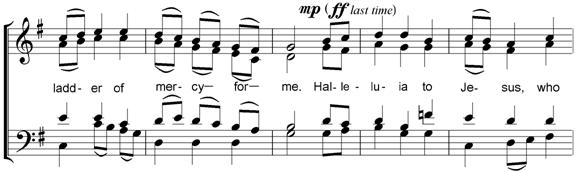

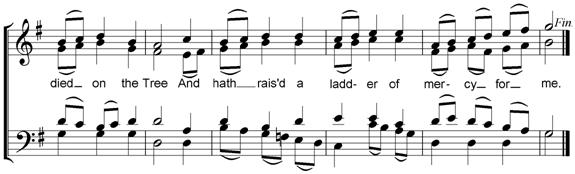

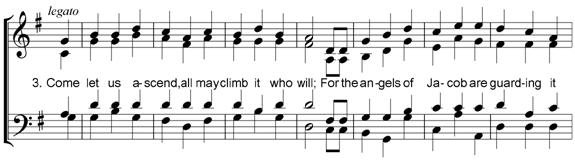

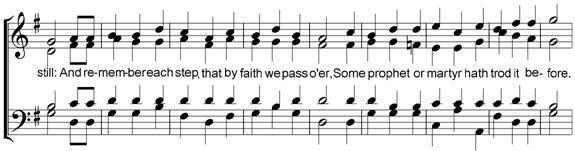

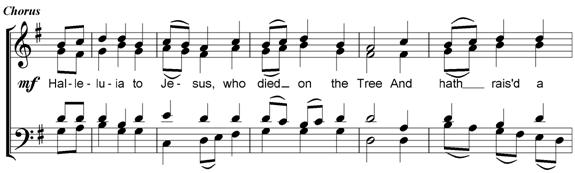

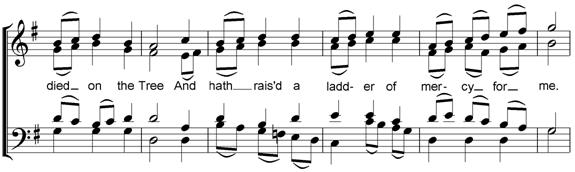

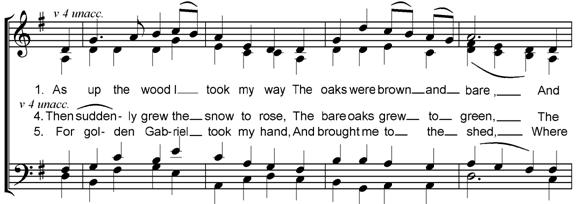

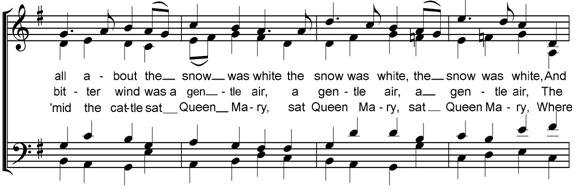

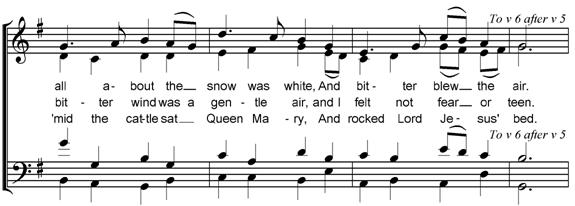

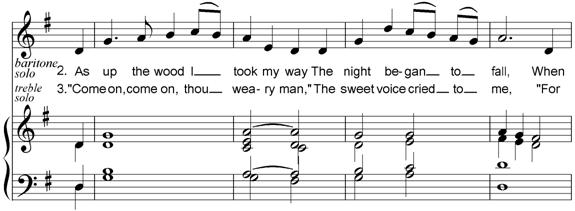

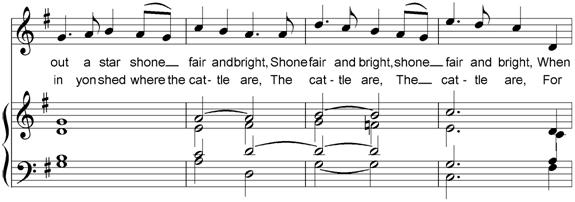

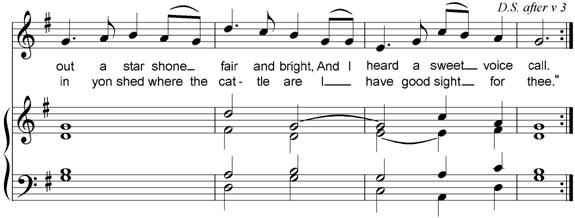

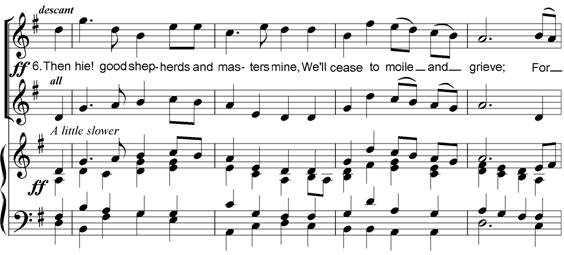

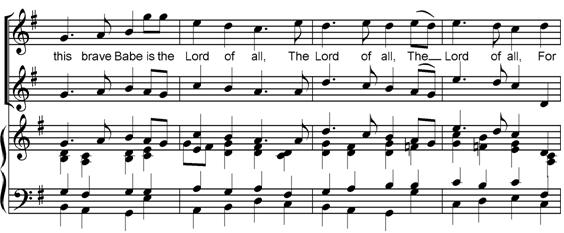

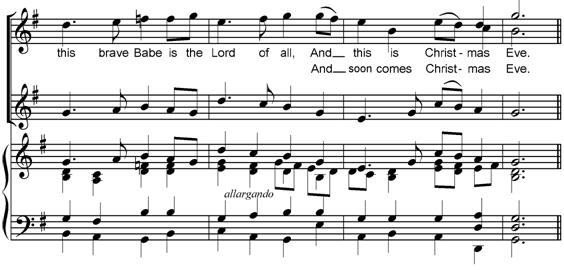

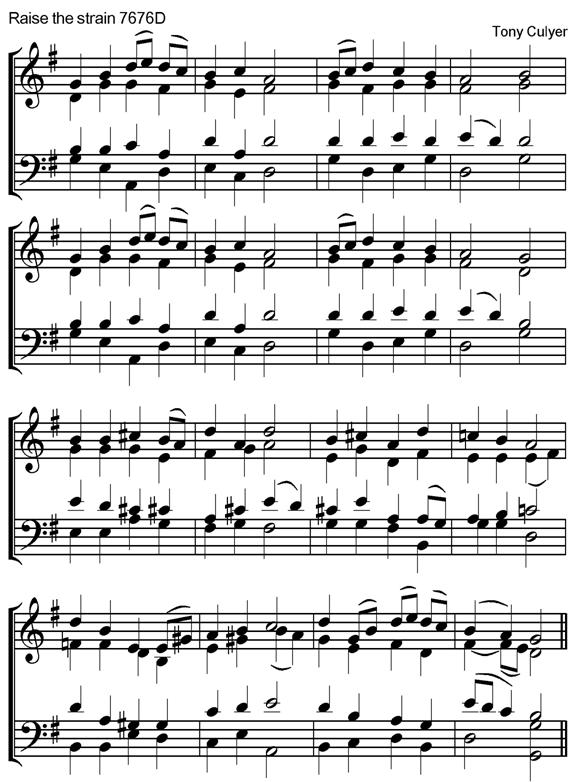

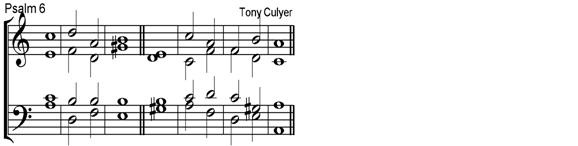

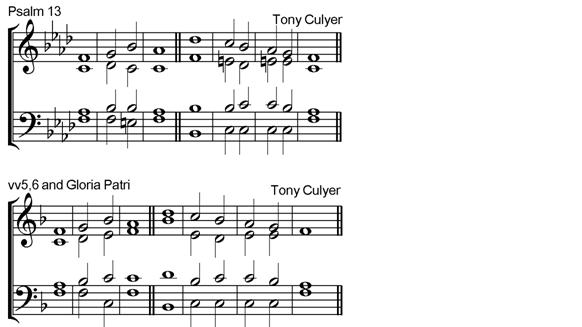

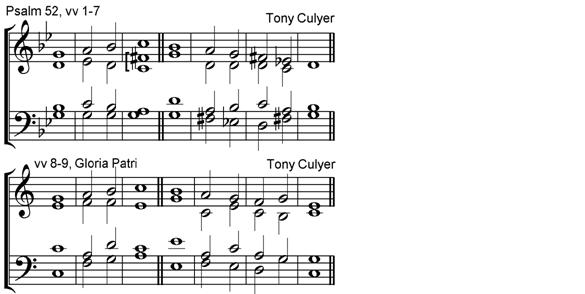

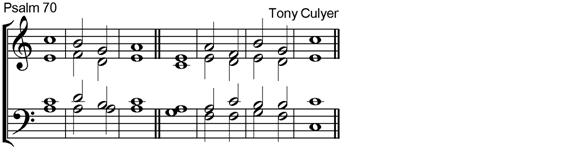

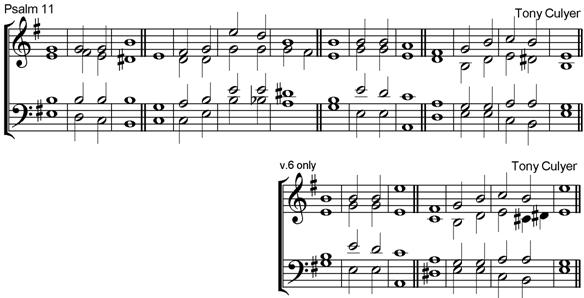

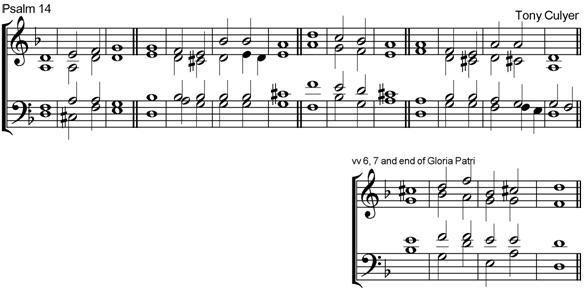

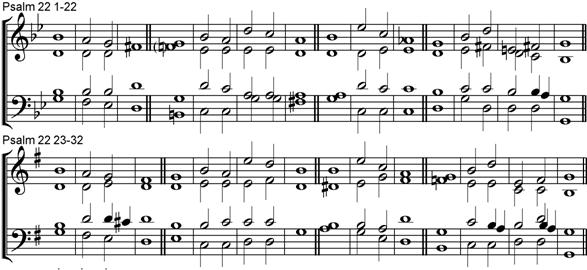

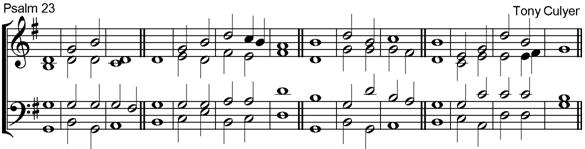

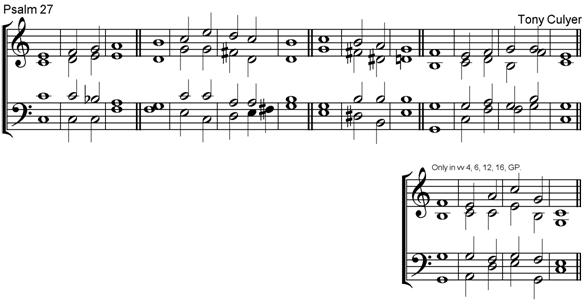

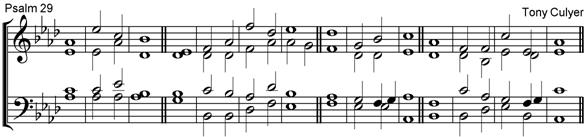

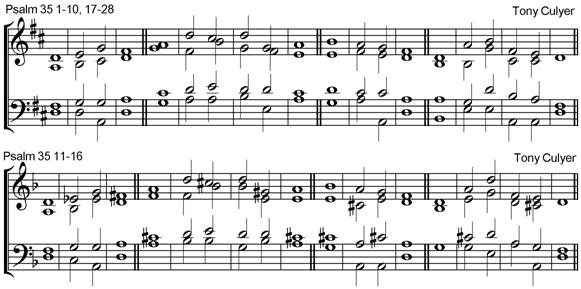

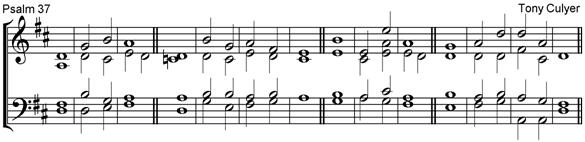

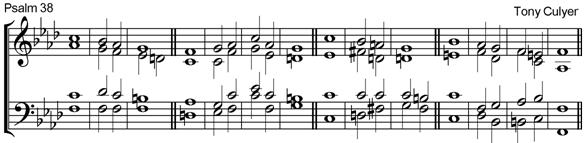

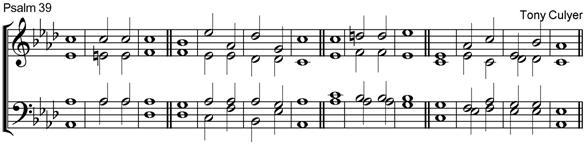

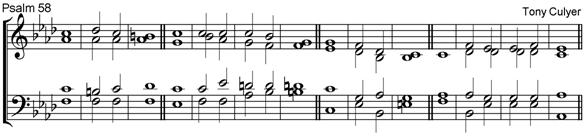

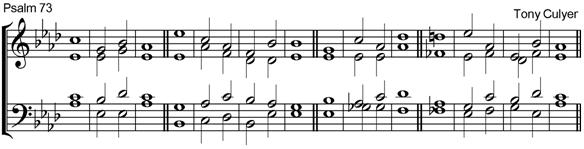

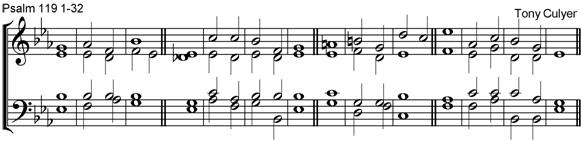

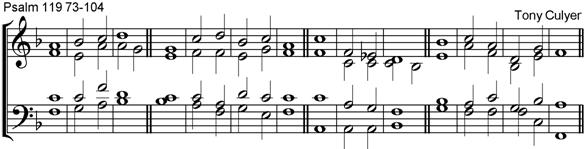

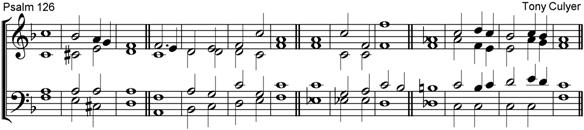

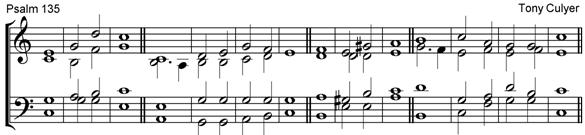

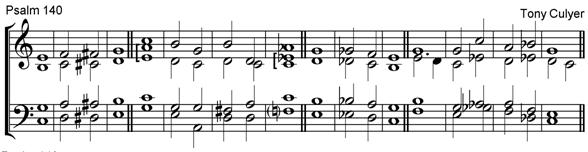

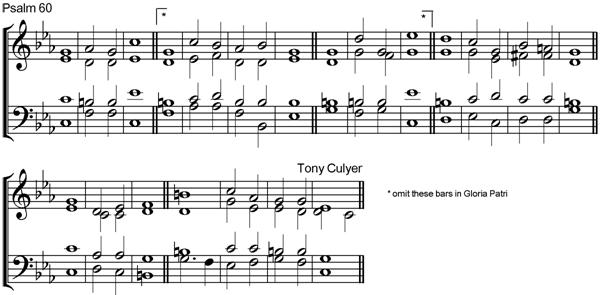

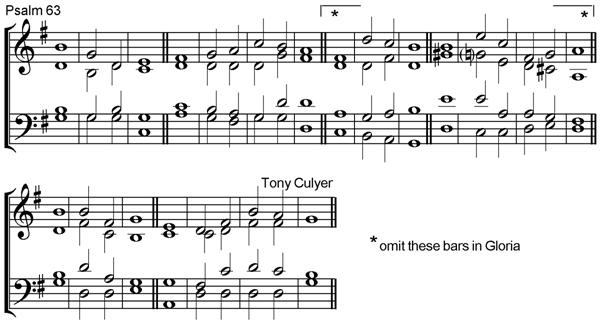

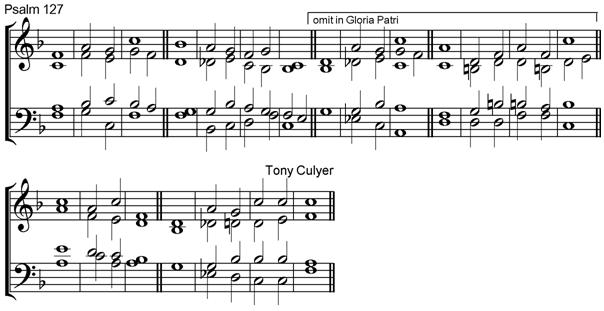

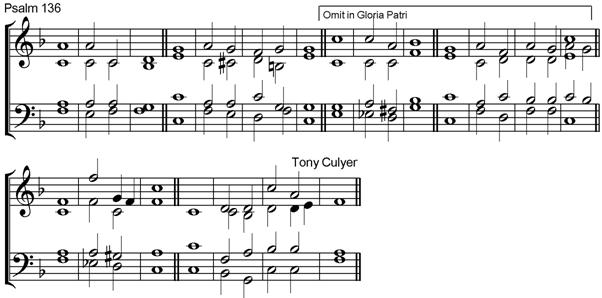

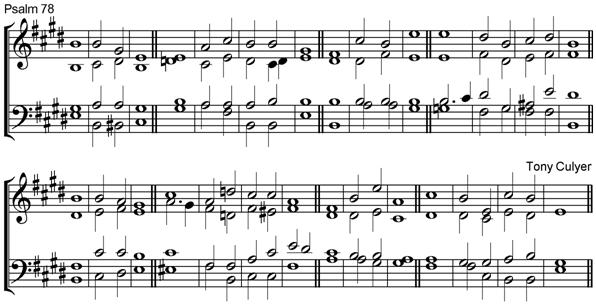

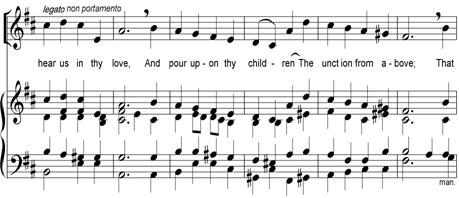

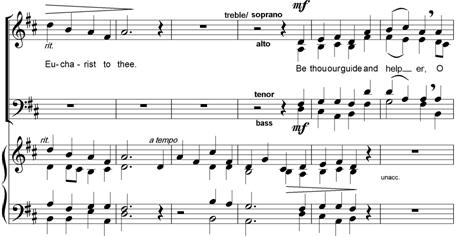

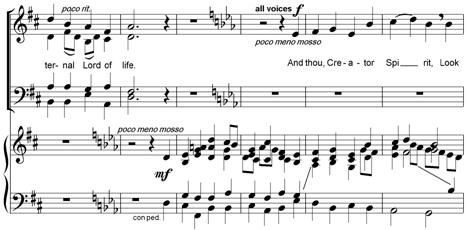

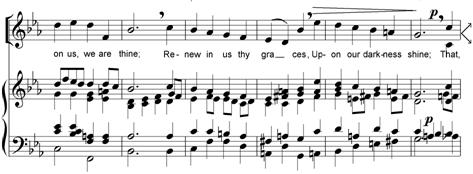

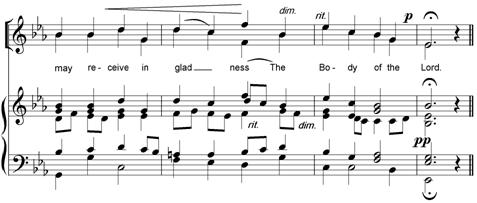

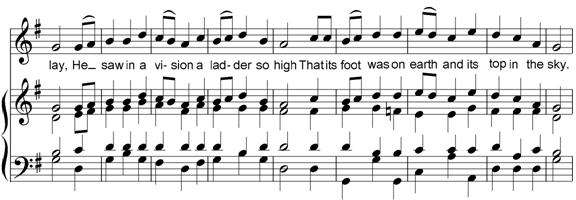

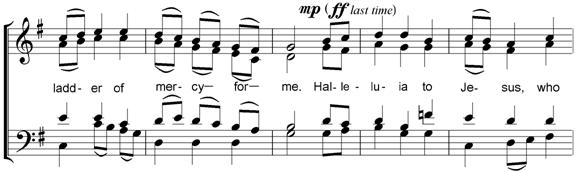

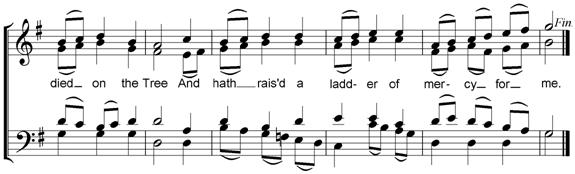

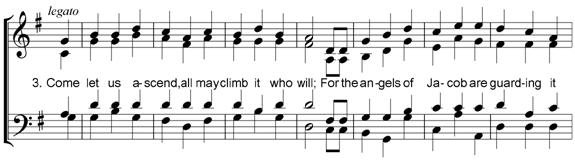

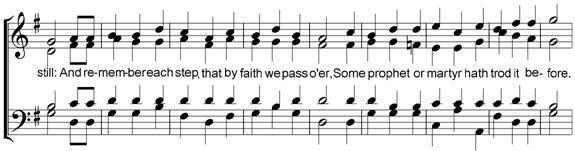

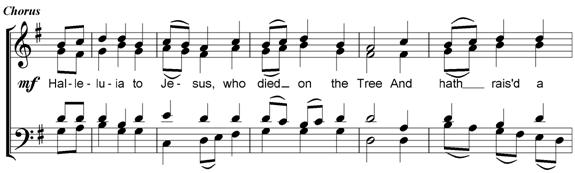

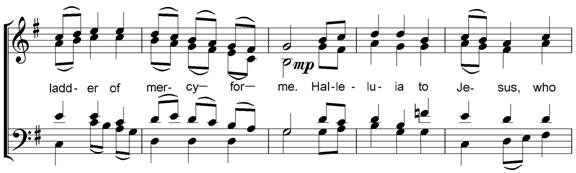

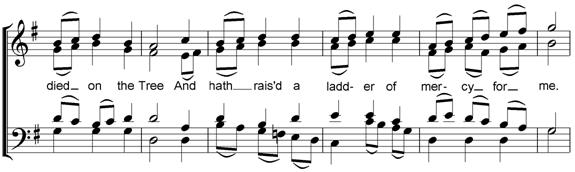

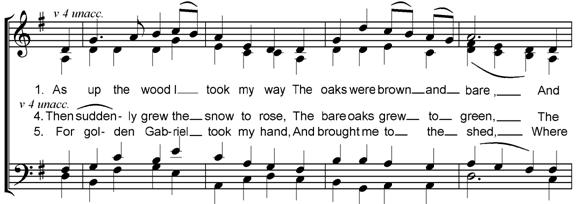

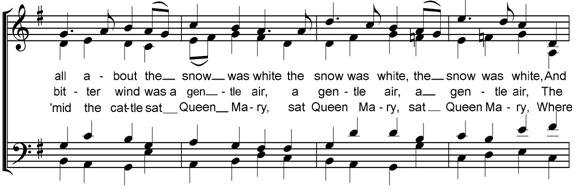

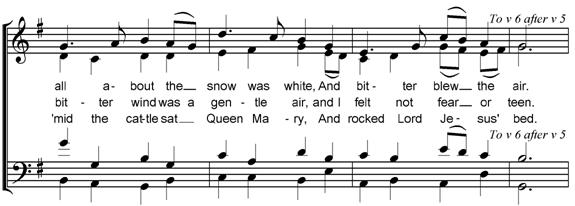

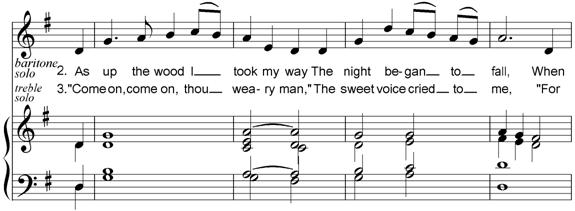

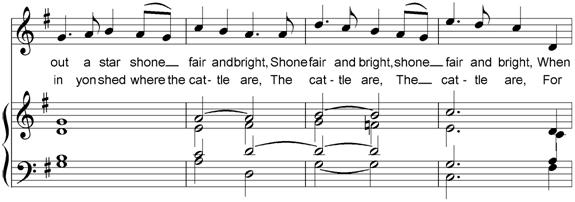

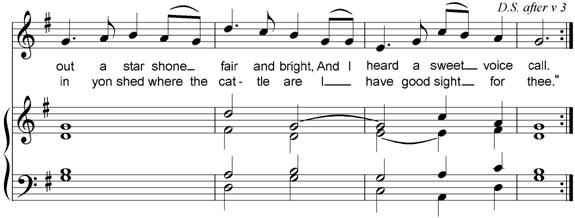

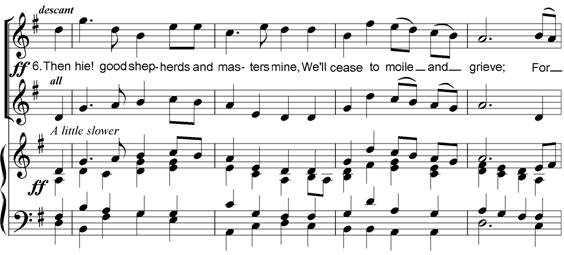

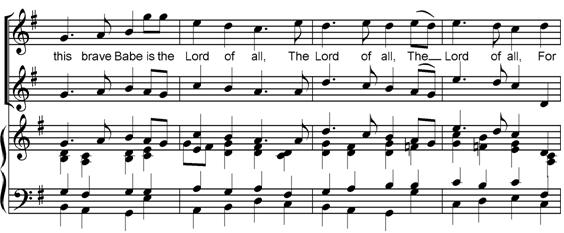

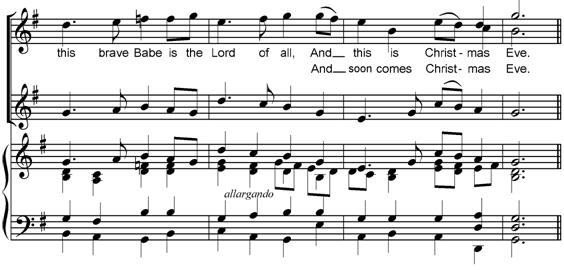

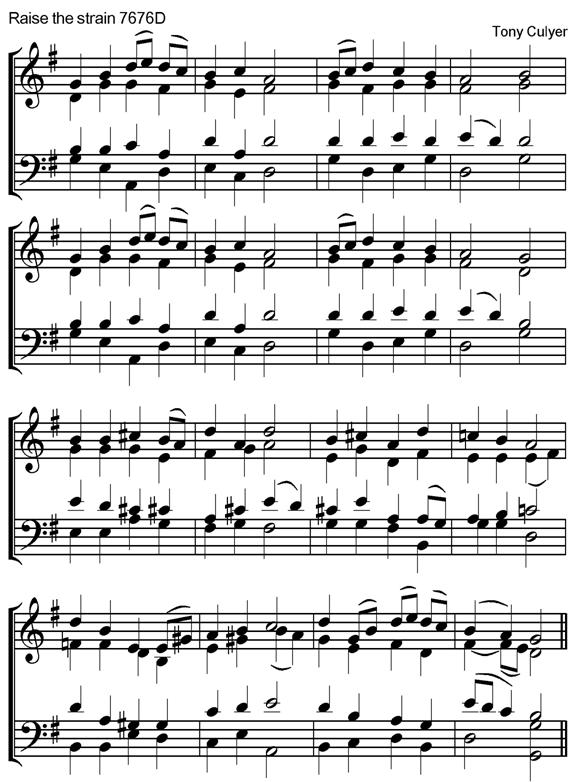

Anglican Chants

Anglican Chants

Other

Pieces

Other

Pieces

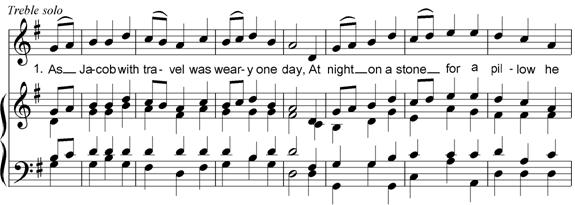

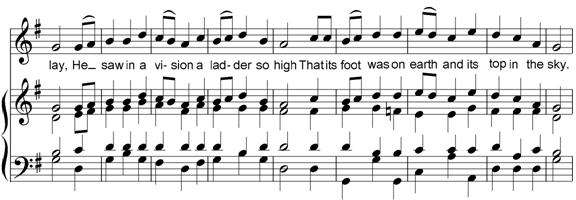

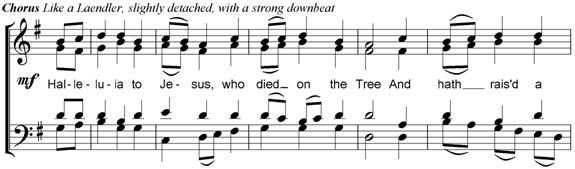

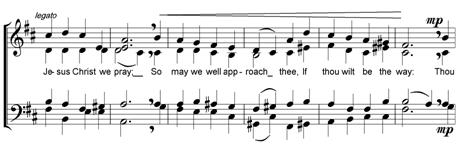

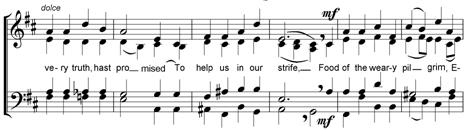

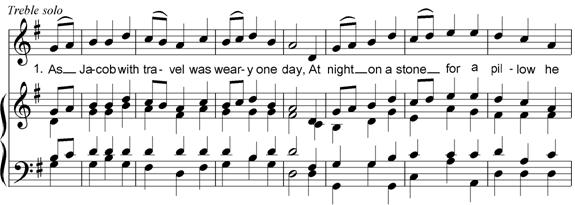

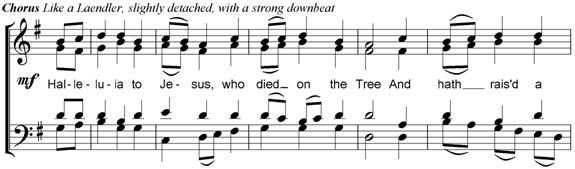

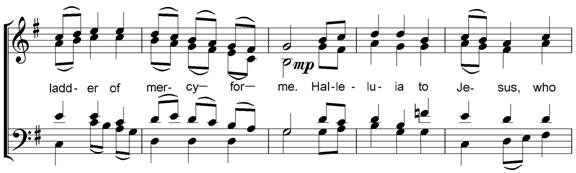

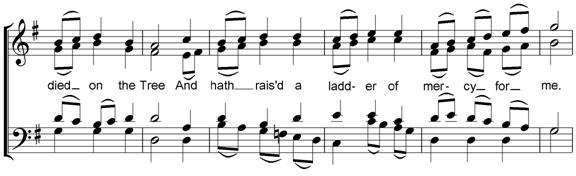

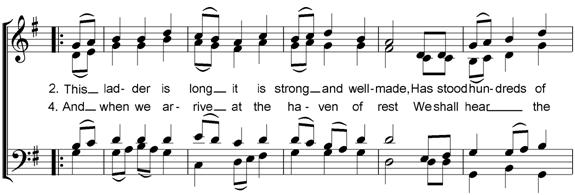

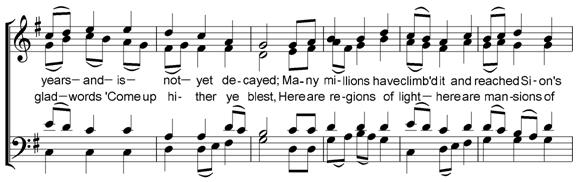

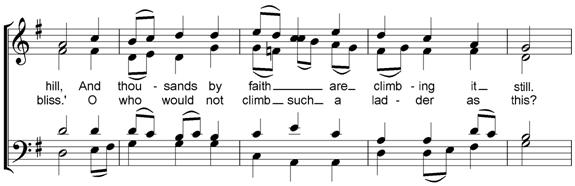

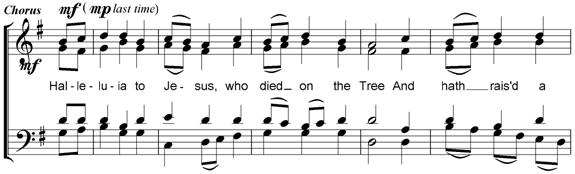

Hymn

Tunes

Hymn

Tunes

Royal

School of Church Music

Royal

School of Church Music

last update: November

2011

Personal background

Present Status

Ontario Research Chair in Health Policy & System Design, University of Toronto

Professor

of Economics, University of York,

England

Adjunct Scientist, Institute for Work and Health, Toronto

Chair,

WSIB Research Advisory Council (to March 2010)

Founding Co-Editor, Journal of Health Economics

Date of Birth

1 July 1942

Addresses

(Home, England): "The Laurels", Main Street, Barmby

Moor, York, Y042 4EJ, UK

Tel.

(0)1759-307177

E-mail: tonyandsiegi@btinternet.com

(Home, Canada):

80 Front Street East Suite 804,

Toronto, Ontario,

M5E 1T4, Canada

Tel: 416

369-9973

E-mail: tonyandsiegi@sympatico.ca

(University,

Canada): Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of

Toronto, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Health Sciences

Building, 155 College Street, Suite 425, Toronto, Ontario M5T 3M6

Tel: 416

978 7340

Fax: 416-978-7350

E-mail: tony.culyer@utoronto.ca

(University, England):

Department of Economics & Related Studies, University

of York, Heslington,

York Y010 5DD, England

Tel: (0)1904-321420

Fax:

(0)1904-433759

E-mail: ajc17@york.ac.uk

Web page: http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~ajc17

Marital Status

Married from 1966 to 2011 to same partner Siegi, with son and daughter,

four grandchildren. Now widowed.

Secondary Education

Sir

William Borlase's School, Marlow

The King's

School, Worcester

University Education

Graduated

Exeter University

in 1964 (2(i)) in Economics, Exeter University

Leo T.

Little Prize for best graduating student in Economics 1964.

1964-5

Graduate Student and Teaching Assistant at the University of California

at Los

Angeles (plus Fulbright Travel Scholarship).

Degrees

B.A. (Hons), (Exeter)

(1964)

Doctor of

Economics, honoris causa

(Stockholm School of Economics) (1999)

Honours

Founding

Fellow of the Academy

of Medical Sciences

(1998)

Commander

of the British Empire (CBE) (1999)

Fellow of

the Royal Society of Arts (1999)

Doctor of

Economics, honoris causa

(Stockholm School of Economics) (1999)

Honorary

Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London (2003)

Fellowships of Academies

Founding Fellow

of the Academy of

Medical Sciences (1998)

Fellow of

the Royal Society of Arts (1999)

Honorary

Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London (2003)

University Career

1964-65 Teaching Assistant, University of California

at Los Angeles

1965-66 Tutor in Economics, University of Exeter

1966-69 Assistant Lecturer in Economics,

University of Exeter.

1969-72 Lecturer in Economics, University of York

1971-79 Assistant

Director, Institute of Social & Economic Research, University of York

1972-76 Senior Lecturer in Economics,

University of York

1976-79 Reader in Economics, University of York

1976 Senior Research Associate at the

Ontario

Economic Council

Visiting Professorial Lecturer at Queen's

University, Kingston, Canada

1979 William

Evans Visiting Professor, University

of Otago, Dunedin, New

Zealand

Visiting Fellow, Australian

National University,

Canberra, Australia

1979-82 Deputy

Director, Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of York

1979- Professor

of Economics, University

of York (since 1982 in

Department of Economics & Related Studies)

1983-84 Director of the Graduate Health Economics Programme,

Department of Economics & Related Studies, University of York

1985-86 Visiting Professor, Trent University,

Canada

1986-01 Head of Department of Economics &

Related Studies, University

of York

1989-94 Visiting

professor, Department of Health Administration, University of Toronto

1990-91 (Oct-Feb)

Visiting Professor, Institut für Medizinische Informatik und Systemforschung

(Gesellschaft für Strahlen-und Umweltforschung), Munich, Germany

1991

(Apr-Sep) Visiting

Professor, Department of Health Administration, University of Toronto

1991-94 Pro-Vice-Chancellor, University of York, England

1994-97 Deputy Vice-Chancellor, University of York, England

1995-96 Director, School

of Politics, Economics &

Philosophy, University

of York

1996

(November) Visiting

Professor, Central Institute of Technology,

New Zealand

1997-01 Director of Health Development, University of York

1999-01 Director (Board Member) of York Health Economics

Consortium

2001-03 Chair, Board of York Health Economics Consortium

2003-07 Visiting

Professor, Department of Health Policy, Management & Evaluation, University

of Toronto

2003-06 Chief

Scientist, Institute for Work &

Health, Canada

2006-07 Senior

Scientist, Institute for Work &

Health, Canada

2006-07 Senior

Economic Adviser, Cancer Care Ontario

2006-10 Chair,

Research Advisory Council of the Workplace Safety & Insurance Board

(Ontario)

2007- Ontario Research Chair in Health Policy and System

Design, University

of Toronto

2007- Adjunct

Scientist, Institute for Work & Health, Toronto

Affiliations

Academy

of Medical Sciences, Health Economists' Study Group, International Health

Economics Association, Royal Economic Society, Royal Society of Arts, Royal

College of Physicians (London), Royal School of Church Music, Royal School of

Church Music (Canada).

Journal Editing

1996-70 Acting

Editor, Assistant Editor, Editorial Board member

(various times), Social and Economic

Administration.

1982- Founding Co-editor, Journal of Health Economics

1984-85 Founding Editor, Nuffield/York Portfolios

1986-96 Advisory Editor, Social Science and Medicine

1976-84 Member, Editorial Board, Bulletin of Economic Research

1983-93 Founding Member, Editorial Panel, The Economic Review

1992-2002 Member, Editorial Board, Medical Law International

1994-2001 Member, Managing Committee, Journal of Medical Ethics

1995-2000 Member, Editorial Board, British Medical Journal

1996-2007 Founding

Member, International Advisory Board, Clinical

Effectiveness in Nursing

1998-2001 Member,

Editorial Advisory Board, Handbook on

Research Methods for Evidence Based Health Care

1999-2005 Member,

Editorial Board, Zeitschrift für die

gesamte Versicherungswissenschaft

2001 Guest Editor, Journal of Medical Ethics (Vol. 27, No.

4).

2009- Editor in Chief, The Elsevier on-line Encyclopedia of Health Economics,

External Academic Advisory

Boards

1989-92 Member,

Methodological Advisory Group on Non-economic Loss, Ontario Workers'

Compensation Board

1992-98 Member,

Advisory Committee of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (Population

Health Program)

1992-2001 Member,

Advisory Committee for Centre for Health and Society, University College,

London

1990-94 Member,

Research Advisory Committee of the Institute for Work and Health (Toronto,

Canada)

1997-2002 Member,

Research Advisory Committee of Canadian Institute for Health and Work

1997-2003 Member,

Research Advisory Committee of the Institute for Work and Health (Toronto,

Canada)

2000-03 Trustee, The

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, Ottawa

2001 Member,

International Scientific Advisory Committee, Unit of Health Economics and

Technology Assessment in Health Care, Budapest University of Economics

2006-10 Member, International Advisory Board,

Alberta Bone & Joint Institute

2006-10 Chair,

Research Advisory Council, Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (Ontario)

2006-10 Member,

Advisory Board, Centre for Research Expertise in Musculo-Skeletal

Diseases, University of Waterloo

2006-10 Member,

Advisory Board, Centre for Research Expertise in Occupational Disease,

University of Toronto

2006-10 Member,

Advisory Board, Centre for Research Expertise in Improved Disability Outcomes,

University Health Network, Toronto

Professional Groups

1970-86 Founding Organiser,

Health Economists' Study Group (HESG)

1970- Member, HESG

1975-76, Member,

Scientific Committee of the International Institute of Public Finance

1975-90 Honorary Adviser

to the Office of Health Economics

1977-85 Member,

Organising Committee of International Seminar in

Public Economics

1979-85 Founding Course Coordinator for the Health Economics

option, Corporate Management Programme of King's Fund College, London

1980-82 Convenor, SSRC European Workshop in Health Indicators (for

report, see publications)

1982-83 Member,

Scientific Committee of the International Institute of Public Finance

1983-84 Director,

York MSc. Programme in Health Economics

1987-88 Member, Institute of Health Service Management Working

Party on Alternative Funding and Delivery of Health Services (for reports see

publications).

1987-2001 Member,

Conference of Heads of University Departments of Economics (CHUDE)

1988-93 Member, Standing Committee of CHUDE

1989-92 Member, College Committee of the

King's Fund College, London,

1990-97 Member

of Editorial Policy Committee, Office of Health Economics

1990-97 Member, Editorial Board, Office of

Health Economics

1991-93 Member,

Economics Association National Development Group on economics curriculum

development

1991-92 Council member,

Royal Economic Society

1992 World

Health Organisation Adviser (economics of schistosomiasis control in Kenya)

1992 Member,

Canadian Institute of Advanced Research (Review Panel on Population Health)

1992-97 Member,

Kenneth J. Arrow Award in Health Economics (Prize Committee)

1992-92 Member,

Institute of Health Services Management's "Future Health Care

Options" Working Party

1994 President, Section F (Economics),

British Association

1996 Member, ESRC Training Board Economics Area Panel

1996-2003 Member, Academic Advisory Council,

University of Buckingham

1997 Member

of World Health Organisation two-person mission to

Kazakhstan on the privatisation and reform of health

care services, February

1997-2001 Vice Chair, Office of Health Economics

1997- Chair, Office of Health Economics

Editorial Board

1988-93 Member, Standing Committee of CHUDE

2001- Chair, Office of Health Economics

Policy Board

2002-07 Member, Governing Board,

International Health Economics Association

2004- Chair, Office of Health Economics

Management Committee

2004-06 Adviser, Canada Health Council

2005 Member, Ontario Health

Technology Advisory Committee

2006-07 Senior Economic Advisor, Cancer Care

Ontario

2006-07 Economic Advisor, Ontario Ministry of

Health and Long Term Care

2006 Member,

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Equity Editorial Board

2006-08 Canadian

Institutes for Health Research Michael Smith Prize in Health Research Committee

2007- Member,

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Career Scientist Relevance Review

Panel

2007- Member,

Ontario Ministry of Health and

Long Term Care Health Research Advisory Council

2009- Member,

Hall Foundation Board (Canada)

2009- Member

Advisory Committee, NICE International

2009- Member,

Department of Health Policy Research Units Commissioning Panel

2009- Member,

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, Health System Strategy Division,

External Advisory Group

2009- Member,

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Advisory Group on Productivity

2009- Member,

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Steering Committee for

Partnerships for Health System Improvement (CIHR project)

2010- 11 Member, Ontario

Health Quality Council Advisory Committee

Principal Lectures

1976 Plenary Lecture, First Canadian

Health Economics Symposium, Kingston

1980 Plenary

Lecture, First Australian Conference of Health Economists, Canberra

1986 Woodward Lecturer, University of

British Columbia

1986 Plenary

Lecture, Third Canadian Conference on Health Economics, Winnipeg

1990 Perey

Lecturer, McMaster University

1990 Champlain Lecturer, Trent

University

1994 Francis

Fraser Lecturer (British Postgraduate Medical Federation, London).

2001 Plenary Lecture Canadian

Health Economics Study Group, Vancouver

2006 Sinclair Lecturer, Queens

University, Kingston

2005 Plenary Lecture, Canadian

Health Economics Study Group, Toronto

University (outside my

Department) Management

1991-94 Pro-Vice-Chancellor, University of

York

1994-97 Deputy Vice-Chancellor

1994-99 Member,

Health Sector Group of the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals

1997-2001 Director of Health Development,

University of York

At

various times Representative of University of York on Court and Council of

Leeds University, 1978-85, member of Council, Nominations Committee, General

Academic Board, Professorial Board, Member or chair of: Staff Committee,

Finance Committee, Secretarial and Clerical Committee, Joint Negotiating

Committee (Joint chair), Court, Council, Appointments to Court and Council,

Vacancies Review Panel, Planning Committee, Administrative Planning Committee,

Policy and Resources Committee, Equipment Subcommittee (minor spenders), VC's

Advisory Group, VC's advisory committees on Academic Plan, Discretionary Salary

Awards; Promotions Committee, Premature Retirement Committee, Leave of Absence

Committee, Research Committee (chair), Awards Sub-Committee (chair), Health

Liaison Group (chair), Board for Graduate Schools (chair), Undergraduate

Admissions Committee (chair), Special Cases Committee (chair), Medical Services

Committee (chair), Library Advisory Committee (chair), Joint Committee with AUT

(chair), Heslington Lectures Committee (chair),

University Committee (chair), King's Manor Resources Group (chair),

Disciplinary Advisory Committee, IT Strategy Committee, Panel for Admin Library

Computing and Other Related Staff (chair), Post-1995 Institutional Planning

Group, Careers Advisory Group (chair), Alcuin Collaboration Group (chair),

Alcuin Project Development Group (chair), Alcuin Project Steering Group

(member), CVCP (in lieu of VC), Search Committee for new VC (1992), chair of

any of the above chaired by VC in his absence, University and University

College of Ripon & York St John Health Collaboration Steering Group

(co-chair).

Principal Canadian Connections

1976 Senior

Research Associate at the Ontario Economic Council and Visiting Professor, Economics

Department, Queens University

1985-6 Visiting Professor, Trent University,

Canada

1986 Woodward Lecturer, University of British Columbia

1989-90 Visiting

Professor, Department of Health Administration, University of Toronto

1989-92 Member,

Methodological Advisory Group on Non-economic Loss, Ontario Workers' Compensation Board

1990 Commissioned to write paper on

Equity in Health for Ontario Premiers Council on Health, Well-Being and Social

Justice

1990 Perey

Lecturer, McMaster

University

1990 Champlain Lecturer, Trent University

1991 (Apr-Sep) Visiting Professor,

Department of Health Administration, University

of Toronto

1990-4

and

1997-02 Member,

Research Advisory Committee, Institute for Work and Health, Toronto

1992-02 Member,

Advisory Committee of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Population

Health Program

2000-3 Trustee,

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, Ottawa

2002-3 Member,

Scientific Advisory Committee, Institute for Work and Health

2003-7 Visiting

professor, Department of Health Policy, Management & Evaluation

, University

of Toronto

2003-6 Chief Scientist,

Institute for Work & Health, Toronto

2003-4 Member, External Research Review Team for

Cancer Care Ontario

2005-7 Adviser, Canada Health Council

2005-6 Member, Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee

(OHTAC)

2005-7 Member,

CIHR Michael Smith Prize in Health Research Committee

2005- Member, Scientific Committee,

Alberta Bone & Joint Health Institute

2006- Member, International Advisory

Board, Alberta Bone & Joint Institute

2006-7 Senior Scientist,

IWH, Toronto

2006- Advisor to MOHLTC on Citizens

Council

2006- Chair, WSIB Research Advisory

Council

2006-7 Senior Economic Advisor, Cancer

Care Ontario

2007 Chair,

External Review Panel of Centre

for Health Service Policy Research, UBC

2006-10 Chair,

Research Advisory Council, Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (Ontario)

2006-10 Member,

Advisory Board, Centre for Research Expertise in Musculo-Skeletal

Diseases, University of Waterloo

2006-10 Member,

Advisory Board, Centre for Research Expertise in Occupational Disease,

University of Toronto

2006-10 Member,

Advisory Board, Centre for Research Expertise in Improved Disability Outcomes,

University Health Network, Toronto

2006 Member, Ontario

Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Equity

Editorial Board

2007- Member,

Value for Money Committee, Health Council of Canada

2007- Member, Ontario

Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Career Scientist Relevance Review Panel

2007- Member, Ontario Ministry of

Health and Long Term Care Citizens Council Advisory Committee

2007- Member, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long

Term Care Health Research Advisory Council

2008- Chair,

Advisory Committee to CCO Pharmaceutical Economics Unit

2008- Member, Advisory Committee, Toronto Health Economics

and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative

2008- Member, Clinical Standards,

Guidelines and Quality Committee of the Board of Cancer Care Ontario

2009- Member, Interim Scientific

Committee, Occupational Cancer Research Centre, Toronto

2009- Member,

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, Health System Strategy Division,

External Advisory Group

2009- Member,

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Steering Committee for

Partnerships for Health System Improvement (CIHR project)

2010- Member,

Ontario Health Quality Council Advisory Committee

Current other roles

Co-editor,

Journal of Health Economics

Chair,

Office of Health Economics (London, England)

Adjunct

Scientist, Institute for Work & Health, Toronto

Trustee

and Council member, Royal School of Church Music

Director,

Royal School of Church Music, Canada

Member,

Citizens Council Committee, NICE

Member,

Advisory Committee, NICE International

Member,

MOHLTC Advisory Committee on Citizens Council

Member,

MOHLTC Advisory Committee on R&D

Member,

editorial boards of several other journals

Member,

International Advisory Board, Alberta Bone & Joint Institute

Member,

Advisory Board, Royal

School of Church Music

Member,

Board of Directors, Royal School of Church Music (Canada)

External Assessor

for Chairs etc.

Durham

(economics), Leeds (health economics), London School of Economics (social

policy), London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (health economics)

(twice), Newcastle (health sciences), Oslo (health economics), Toronto (health

economics), Southampton (health policy), UBC (economics) (twice)Northallerton Health Authority (Chief Executive), Office of

Health Economics (deputy director), King's Fund (Chief Executive), National

Institute for Clinical Excellence (Director of Appraisals), North Yorkshire

Health Authority (Director of Primary Care), Director of R&D (NICE).

External Reviews of

Departments

1989 Economics Department, McMaster

University

1993 London Special Health

Authorities (member of Thompson Committee)

1998 Wessex Institute and the Institute of Health Policy,

Southampton University (with Charles Florey) 1

1999 McMaster

University Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis (CHEPA)

2007 UBC Centre for Health Services

Policy Research

National Health Service

(England) Appointments

1975-84 Member, DHSS

Research Liaison Groups (several)

1982-90 Member, Northallerton

Health Authority

1990-92 Non-executive member,

Northallerton Health Authority

1991-2001 Member,

Central Research and Development Committee (CRDC) for the National Health

Service

1992-93 Member,

Central R&D Committee Mental Health National Steering Group (Goldberg

Committee)

1992-94 Member, Yorkshire Health Research and

Development Committee

1992-97 Member, CRDC Standing Group on Health

Technology

1993-97 Chair, CRDC Health Technology

Assessment (HTA) Methodology Panel

1992-93 Member,

Review Advisory Committee on the London Special Health Authorities. (The

"Thompson Report, Special Health Authorities: Research Review, London,

HMSO, 1993, chaired by Sir Michael Thompson)

1993-94 Chair,

NHS Research Task Force on R&D to Review the Funding and Support of

Research and Development in the NHS, (The "Culyer Report): Supporting Research and Development in the

NHS: A Report to the Minister of Health, London, HMSO, 1994

1994-99 Deputy

Chair and non-executive member, North Yorkshire Health

Authority

(reappointed to new Authority in 1996), (chair and member of several

subcommittees of the Board)

1995-2001 Member, Northern & Yorkshire Regional

Research Advisory Group

1995-2001 Member, Northern and Yorkshire Regional

Universities Group for R&D

1995-99 Special

Adviser, High Security Psychiatric Services Commissioning Board (HSPSCB)

1995-1999 Member, R&D Committee of the HSPSCB

1995-99 Member, R&D Commissioning Sub

Group of the HSPSCB

1996 Member,

Central R&D Committee Sub-Group on the Strategic Framework

1996-97 Member,

National Working Group on R&D in Primary Care (Mant

Committee)

1997-98 Chair,

Department of Health Expert Workshop on DH Guidelines for Pharmaco-economic

studies

1997-98 Adviser,

Department of Health Comprehensive Spending Review Group on "Non

front-line services"

1997-99 Special Adviser

to NHS Director of R&D

1997-98 Chair,

Central R&D Committee Sub-Group on Budget 1 Allocations to Trusts

1998-2002 Member,

Healthcare Sector Group, Department of Trade and Industry and Department of

Health Overseas Trade Services

1998-2000 Member, NHS R&D Exceptional Cases

Advisory Group

1998-2000 Member, NHS R&D Strategic Review Sub

Group

1998-2000 Member, NHS R&D Evaluation Strategy

Steering Group

1999-2003 Vice

Chair (and non-executive director), National Institute for Clinical Excellence

2007-10 Chair, NICE

Research & Development Committee

2007- Member, NICE

Citizens Council Committee

2008- Member, NICE

International Advisory Committee

2008 Member,

Department of Health Value Focus Group on the cost and benefit perspective of

NICE

Other

Government roles

1983-87 Member, Comac-HSR

Committee of the European Commission

1995-97 Member, British Council Health

Advisory Committee

1997-98 Member,

Department of Trade and Industry Advisory Committee on Exports of Health-related

Products

2005-07 Member, Economics Advisory Panel,

Home Office

Recent

publications (2007-10)

2007

Culyer A J. Need - an

instrumental view in Richard Ashcroft, Angus Dawson, Heather Draper and John

McMillan (Eds.) Principles of Health Care

Ethics, 2nd Edition, Chichester: Wiley, 2007, 231-238.

Culyer

A J. When and how cancer chemotherapy should be privately funded," Oncology Exchange, 2007, 6: 47.

Culyer A J, McCabe C, Briggs AH,

Claxton K, Buxton M, Akehurst RL, Sculpher M and Brazier J. Searching for a

threshold, not setting one: the role of the National Institute of Health and

Clinical Excellence, Journal of Health

Service Research and Policy, 2007, 12: 56-59.

Robson

LS, Clarke J, Cullen K, Bielecky A, Severin C, Bigelow P, Irvin E, Culyer AJ, Mahood Q. The

Effectiveness of Occupational Health and Safety Management System

Interventions: A Systematic Review, Safety

Science, 2007, 45: 329-353.

Culyer A J Merit goods and the welfare economics of coercion in Wilfried Ver Eecke (Ed.) Anthology regarding Merit Goods. The Unfinished

Ethical Revolution in

Economic Theory. West Lafayette: Purdue University

Press, 2007, 174-200 (reprinted from Public

Finance, 1971, 26: 546-572.

Claxton K and Culyer A J,

Rights, responsibilities and NICE: A Rejoinder to Harris Journal of Medical Ethics, 2007, 33: 462-464.

Culyer A J, NICE misconceptions The Lancet, September 11 2007, on-line at http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS014067360761321X/comments

Culyer A J, Equity of what in health care? Why

the traditional answers don't help policy - and what to do in the future HealthcarePapers, 2007,

8(Sp): 12-26.

Culyer A J, McCabe C, Briggs

A, Claxton K, Buxton M, Akehurst

R, Sculpher M, Brazier J, Searching

for a threshold - Not so

, Journal of Health Services

Research and Policy, 2007, 12:

190-191. (letter: reply to G Mooney, J Coast, S

Jan, D McIntyre, M Ryan and V Wiseman).

Culyer A J, Resource allocation in health care:

Alan Williams decision maker, the

authority and Pareto, in A Mason & A Towse (eds.) The

Ideas and Influence of Alan Williams:

Be Reasonable Do it My Way! Oxford,

Radcliffe Publishing, 2007, 57-74.

2008

E Tompa, A J Culyer, R Dolinschi (Eds.) Economic Evaluation of Interventions for

Occupational Health and safety: Developing Good Practice, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp.

xvi + 295.

Chalkidou K, Culyer A J, Naidoo B, Littlejohns P Cost-effective

public health guidance: asking questions from the decision-maker's

viewpoint, Health Economics,

2008, 17: 441-448.

Claxton K, Briggs A, Buxton M, Culyer A J, McCabe C, Walker S,

Sculpher M J Value based pricing for

NHS drugs: an opportunity not to be missed? British Medical Journal,

2008, 336: 251-254.

Brouwer W B F, Culyer A J, Job N,

van Exel A, Rutten F

F H. Welfarism vs. extra-welfarism, Journal of Health Economics, 2008, 27: 325338.

J Hurley, D Pasic, J Lavis, A

J Culyer C Mustard and W Gnam, Parallel payers and preferred access: how

Canadas Workers Compensation Boards expedite care for injured and ill

workers, HealthcarePapers,

2008, 8: 6-14.

J Hurley, A J Culyer, W Gnam, J Lavis, C Mustard and D

Pasic, Response to commentaries, HealthcarePapers, 2008, 8: 52-54.

K Chalkidou, T Walley, A J Culyer, P Littlejohns, and A Hoy. Evidence-informed

evidence-making, Journal of Health

Services Research & Policy, 2008, 13: 167-173.

K Claxton and A J Culyer Not a NICE fallacy: A reply to Dr Quigley, Journal of Medical Ethics 2008, 34:

598-601.

A J Culyer, B Amick and A LaPorte. What is a little more health and safety worth?

in E Tompa, A J Culyer, R Dolinschi (Eds.) Economic Evaluation of Interventions for

Occupational Health and safety: Developing Good Practice, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, 15-35.

A J Culyer and M Sculpher. Lessons from health technology

assessment in E Tompa, A J Culyer,

R Dolinschi (Eds.) Economic Evaluation of

Interventions for Occupational Health and safety: Developing Good Practice,

Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2008, 51-69.

A J Culyer

and E Tompa.

Equity, in E Tompa, A J Culyer, R Dolinschi (Eds.) Economic

Evaluation of Interventions for Occupational Health and safety: Developing Good

Practice, Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2008, 215-231.

E Tompa, A J Culyer and R Dolinschi

Suggestions for a reference case, in E Tompa, A J Culyer, R Dolinschi (Eds.) Economic

Evaluation of Interventions for Occupational Health and safety: Developing Good

Practice, Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2008, 235-244.

C McCabe, K Claxton and A J Culyer The NICE

cost effectiveness threshold what it is and what that means, PharmacoEconomics,

2008,

26: 733-744.

K Chalkidou, A J Culyer, P Littlejohns, P Doyle, A Hoy. Imbalances in funding for clinical and public health

research in the UK:

can NICE research recommendations make a difference? Evidence and Policy, 2008, 4: 355-369.

J Hurley, D

Pasic, J Lavis, C Mustard, A J Culyer,

W Gnam. Parallel

lines do intersect: interactions between the workers compensation and

provincial

publicly financed health care systems in Canada. HealthCare Policy, 2008, 3: 100-112.

2009

Chalkidou K, A J

Culyer, B Naidoo, P Littlejohns "The challenges of developing

cost-effective public health guidance: a NICE perspective", in S Dawson

and Z S Morris (eds.) Future Public

Health: Burdens, Challenges and Opportunities, Basingstoke:

Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, 276-291.

A J Culyer, Deliberative

Processes in Decisions about Health Care Technologies: Combining Different

Types of Evidence, Values, Algorithms and People, London: Office of Health

Economics, 2009, pp. 1-20.

A J Culyer How

Nice is NICE? A Conversation with Anthony Culyer, Health Care Cost

Monitor, Hastings Centre Blog, 2009.

M. J. Dobrow, R. Chafe, H. E. D. Burchett, A J Culyer, L. Lemieux-Charles Designing Deliberative Methods for Combining Heterogeneous Evidence: A

Systematic Review and Qualitative Scan. A Report to the Canadian Health

Services Research Foundation, Ottawa:

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, 2009, pp. 24 + 30, ().

2010

Cookson

R, A J Culyer. Measuring overall population health - the use

and abuse of QALYs, in Killoran A, Kelly M (eds). Evidence

Based Public Health: Effectiveness and Efficiency, Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2010, 148-168.

A J Culyer, The Dictionary of Health Economics,

Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2010.

A J Culyer "Perspective and desire in comparative effectiveness research - the relative unimportance of mere preferences, the central importance of context", Pharmacoeconomics, 28: 1-9.

2011

K Claxton, M

Paulden, H Gravelle, W Brouwer, A J

Culyer. Discounting and decision making in the

economic evaluation of health-care technologies, Health Economics, 2011, 20: 2-15.

R Chase, A J Culyer, M Dobrow, P Coyte, C Sawka, S OReilly, K Laing, M

Trudeau, S Smith, J Hoch, S Morgan, S Peacock, R Abbott, T Sullivan. Access to

Cancer Drugs in Canada: Looking Beyond Coverage Decisions, Healthcare Policy, 2011, 6: 27-35.

A J Culyer. UK report: NHS

reforms, Health Care Cost Monitor,

2011, 1-2. The Hastings Centre, on-line at http://healthcarecostmonitor.thehastingscenter.org/anthonyculyer/u-k-report-nhs-reforms.

P Tso, A J

Culyer, M Brouwers, M J Dobrow. Developing a

decision aid to guide public sector health policy decisions: A study protocol,

Implementation Science, 2011, 6:46.

Current

grants

Strengthening the health system

through improved priority setting. Canadian Institutes of Health Research

(Sustainable Financing, Funding and Resource Allocation), Co-investigators: Dr.

Andreas Laupacis

(PI), Dr. Doug Martin (Co-PI_, Dr.

W. Evans, Dr. W. Levinson, Dr. T. Sullivan, Dr. S. Pearson, Dr. A. Hudson.

$159,805 per year for 5 years, 04/2005 to 09/2010.

Dynamics of Parallel Systems of Finance:

Interactions Between Canada's Worker Compensation

Systems and Public Health Care Systems; Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Co-investigators: Dr Jerry Hurley

(PI), Dr William Gnam, Dr John Lavis, Dr Cameron

Mustard, Dr Emile Tompa.

$75,000 for 1 year, Reference #: PPG-74820.

Several grant applications to CIHR with M

Dobrow (Cancer Care Ontario)

and others are currently being considered.

Recent

grant

Conceptualising and Combining

Evidence for Health System Guidance, Canadian Institutes of Health Research,

Co-investigator Dr Jonathan Lomas,

2005.

Teaching

Experience

Graduate

At various times have given lectures and

seminars in Advanced Economic Theory (micro and macro), the Economics of Human

Resources, the Economics of Social Policy, Health Economics, Social Policy

Analysis, and given graduate classes on Social Policy to students of Social

Administration. Supervised MSc, MPhil and DPhil thesis students.

PhD external examiner at various Universities in the UK and

overseas.

Undergraduate

At various times have given first year

introductory lectures in Economics; second year lectures in Price Theory,

Welfare Economics, Macroeconomics, and Investment Appraisal; third year

lectures and seminars in Economics of the Social Services, Economics of Human

Resources, Health Economics, Applied Economics, and Advanced Economic Theory. External examining.

Listed

in

At various times:

Who's Who in Economics: A Biographical

Dictionary of Major Economists 1700-1981 (ed. Blaug

and Sturges), Wheatsheaf,

1983 (and subsequent editions)

Who's Who

Who's Who in Education

Whos Who in America

Whos Who in the World

The Academic Who's Who

The Universities' Who's Who

The International Authors' and Writers' Who's

Who

People of Today

Recreation

and other

Church music: Emeritus Organist and Choir

Director in an Anglican rural parish church in England, Chair of the York

District of the Royal School of Church Music 1983-95, Chair of North East Area

Committee of the Royal School of Church Music 1995-2003, member RSCM Advisory

Board 2002-4, Member of Council and Trustee RSCM, 2003-. Board

Director of Royal School of Church Music (Canada) 2008-. Member of the York Diocesan Liturgy and

Music Advisory Group 1995-99. Various roles in local Church of England (at various

times Parochial Church Council member, Lay Chair of Parochial Church Council,

Sometime Deanery Financial Adviser, Sometime Member York Diocesan Church Urban

Fund, etc.). Amateur composer. Music

generally. Gardening when time, weather and low back problems permit.

DIY when time and LBP permit and urgency insists.

PUBLICATIONS

A.

Articles

1.

A J Culyer. "Methodological error in

regional planning: the South West Strategy", Social and Economic Administration, 1968, 2: 23-30.

2.

A J Culyer. "Holidays on the move", New Society, 11 April, 1968.

3.

A J Culyer, D C Corner "University

teachers and the PIB", Social and

Economic Administration, 1969, 3:

127-139.

4.

F

M M Lewes, A J

Culyer, G A Brady. "The holiday industry" in British Association,

Exeter and its Region, Exeter: University

of Exeter. 1969, 244-258.

5.

A J Culyer. "Pricing policies" in G. Teeling-Smith (ed.), Economics

and Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry, London: Office of Health Economics, 1969,

35-50.

6.

A J Culyer. "The economics of health

systems" in The Price of Health,

Melbourne: Office of Health Care Finance, 1969, 36-62 (reprinted as ch.7 in J.

R. G. Butler and D. P. Doessel (eds.), Health Economics: Australian Readings,

Sydney: Australian Professional Publications, 1989, 145-66).

7.

M

H Cooper, A J Culyer. "An

economic assessment of some aspects of the organisation

of the NHS" in BMA, Health Services

Financing, London:

British Medical Association, 1970, 187-250.

8.

A J Culyer. "A utility-maximising

view of universities", Scottish Journal

of Political Economy, 1970, 17:

349-68.

9.

A J Culyer, A K Maynard. "The cost of

dangerous drugs legislation in England

and Wales",

Medical Care, 1970, 8: 501-509.

10.

M

H Cooper, A J Culyer. "An

economic survey of the nature and intent of the British National Health

Service", Social Science and

Medicine, 1971, 5: 1-13.

11.

A J Culyer. "Ethics and economics in blood

supply", Lancet (i) March 1971.

12.

A J Culyer. "Social scientists and blood

supply", Lancet (i) June 1971.

13.

A J Culyer. "The nature of the commodity

'health care' and its efficient allocation", Oxford Economic Papers, 1971,

23: 189-211 (reprinted as Ch. 2 in

A. J. Culyer and M. H. Cooper (eds.), Health

Economics, London: Penguin, 1973, also in A J Culyer (Ed.) Health Economics: Critical Perspectives on

the World Economy, London: Routledge, 2006,

148-157).

14.

A J Culyer. "Medical care and the

economics of giving", Economica, 1971, 38:

295-303 (reprinted as Ch. 18 in M. Ricketts (ed.), Neoclassical Microeconomics, Vol. 2, Aldershot:

Edward Elgar, 1989, pp. 310-18).

15.

A J Culyer. "A taxonomy of demand

curves", Bulletin of Economic

Research, 1971, 23: 3-23.

16.

A J Culyer. "Calculus of health", New Society, 23 September, 1971.

17.

A J Culyer, A Williams, R J Lavers. "Social

indicators: health", Social Trends,

1971, 2: 31-42 (reprinted as Health indicators in

Andrew Shonfield and Stella Shaw (eds.) Social Indicators and Social Policy, London: Heinemann, 1972).

18. A J Culyer.

"Merit goods and the welfare economics of coercion", Public Finance, 1971, 26:

546-72. (Reprinted in Wilfried

Ver Eecke

(2006) Merit Goods: The Birth of a New

Concept. The Unfinished Ethical Evolution in Economic Theory. Ashland Ohio: Purdue University

Press, 174-200).

19.

A J Culyer. "Appraising government spending

on health services: The problems of 'need' and 'output'", Public Finance, 1972, 27: 205-11.

20.

A J Culyer. "On the relative efficiency of

the National Health Service", Kyklos, 1972, 25: 266-287.

21.

A J Culyer."The market versus the state

in medical care: a minority report on an empty academic box", in G.

McLachlan (ed.), Problems and Progress in

Medical Care, 7, London:

Oxford University Press, 1972, 1-32.

22.

M

H Cooper, A J Culyer. "Equality

in the NHS: intentions, performance and problems in evaluation", in M. M.

Hauser (ed.), The Economics of Medical

Care, London:

Allen and Unwin, 1972, 47-57.

23.

A J Culyer, A Williams, R J Lavers. "Social

indicators: health" in A. Shonfield and S. Shaw

(eds.) Social Indicators and Social

Policy, London, Heinemann, 1972, (reprint of 1971 article in Social Trends).

24.

A J Culyer. "Comment on Problems of

Efficiency", in M. M. Hauser, Hauser (ed.), The Economics of Medical Care, London: Allen and Unwin,

1972, 42-46

25.

A J Culyer, P Jacobs. "The War and public

expenditure on mental health - the postponement effect", Social Science and Medicine, 1972, 6: 35-56.

26.

A J Culyer. "Indicators of health: an

economist's viewpoint ", in Evaluation

in the Health Services, London:

Office of Health Economics, 1972, 23-28.

27.

A J Culyer. "Lefficienza relativo del

Servizio Sanitario Nazionale Brittanico", Citta e Societa, 1972, March/April, 35-53.

28.

A J Culyer. "Social policy and government

spending", Local Government Finance,

1972, 76: 353-357.

29.

A J Culyer. "Economic analysis - its

practice and pitfalls", Local

Government Finance, 1972, 76:

385-389.

30.

A J Culyer. "Pareto, Peacock and Rowley,

and the public regulation of natural monopoly", Journal of Public Economics, 1973, 2: 89-95.

31.

A J Culyer. "Should social policy concern

itself with drug 'abuse'?", Public

Finance Quarterly, 1973, 1:

449-456.

32.

A J Culyer. "Hospital waiting lists",

New Society, 16 August, 1973.

33.

A J Culyer. "Is medical care

different?" in A. J. Culyer and M. H. Cooper (eds.) Health Economics, London:

Penguin, 1973, 49-74 [reprint with changes of 1971 article in Oxford Economic

Papers].

34.

A J Culyer. "Hospital waits", New Society, 6 December, 1973.

35.

A J Culyer. "Quids

without quos - a praxeological approach", in A.

A. Alchian et

al. The Economics of Charity, London: IEA, 1973, 35-61.

36.

M

H Cooper, A J Culyer. "The

economics of giving and selling blood", in A. A. Alchian

et al. The Economics of Charity, London, IEA, 1973,

111-143.

37.

J

G Cullis, A J

Culyer. "Private patients in NHS hospitals: subsidies and waiting

lists", in M. Perlman (ed.), The

Economics of Health and Medical Care, International Economics Association.,

London:

Macmillan, 1974, 108-116.

38.

A J Culyer. "Economics, social policy and

disability", in Dennis Lees and Stella Shaw (eds.), Impairment, Disability and Handicap, London: Heinemann for the SSRC, 1974, 17-29.

39.

A J Culyer. "Dialogue on blood 1", New Society, 24 March, 1974.

40.

A J Culyer. "Hospitals",

New Society, 20 June, 1974.

41.

A J Culyer. "Introduction" to University Economics, (3rd Ed.) by A. A.

Alchian and W. R. Allen, Prentice-Hall International,

1974.

42.

R

L Akehurst, A

J Culyer. "On the economic surplus and the value of life", Bulletin of Economic Research, 1974, 26: 63-78

43.

A J Culyer. "The economics of health"

in R. M. Grant and G. K. Shaw (eds.),

Current Issues in Economic Policy, London:

Philip Allan, 1975, 151-173.

44.

A J Culyer. "Value for money in

health", New Society, March

1975.

45.

A J Culyer, J G Cullis.

"Hospital waiting lists and the supply and demand of inpatient care",

Social and Economic Administration,

1975, 9: 13-25.

46.

A J Culyer, J Wiseman, J Posnett.

"Charity and public policy in the U.K.: the law and the

economics", Social and Economic

Administration, 1976, 10: 32-50.

47.

J

G Cullis, A J

Culyer. "Some economics of hospital waiting lists in the NHS", Journal of Social Policy, 1976, 5: 239-264.

48.

A J Culyer. "Discussion of 'Health Costs

and Expenditures in the U.K.'

by M. H. Cooper", in Tei-wei Hu

(Ed.) International Health Costs and

Expenditures, Washington

D.C.: U.S. Department of Health

Education and Welfare, 1976, 109-113.

49.

A J Culyer. "Alternatives to price

rationing: some unsolved riddles for British health economists", in R. D.

Fraser (ed.), Health Economics Symposium,

Proceedings of the First Canadian Conference, Kingston

(Ontario):

Industrial Relations Centre, Queen's University, 1976, 66-74.

50.

A J Culyer, J Wiseman. "Public economics

and the concept of human resources", in Victor Halberstadt

and A. J. Culyer (eds.) Human Resources

and Public Finance, (eds.), Paris: Cujas, 1977, 13-29.

51.

A J Culyer. "Blood and altruism: an

economic review", in D. B. Johnson (ed.), Blood Policy - Issues and Alternatives, Washington

D.C: American Enterprise Institute, 1977, 39-58.

52.

A J Culyer. "The quality of life and the

limits of cost-benefit analysis", in L. Wingo

and A. Evans (eds.), Public Economics and

the Quality of Life, Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins, 1977, 141-153.

53.

A J Culyer. "Drugs and Pareto - a

methodological abuse", Public Finance

Quarterly, 1977, 5: 393-396.

54.

A J Culyer. "Need, values and health

status measurement", in A. J. Culyer and K. G. Wright (eds.), Economic Aspects of Health Services,

London: Martin Robertson, 1978, 9-31.

55.

M

F Drummond, A J Culyer.

"Financing medical education - interrelationships between medical school

and teaching hospital expenditure", in A. J. Culyer and K. G. Wright

(eds.), Economic Aspects of Health

Services, London: Martin Robertson, 1978, 123-140.

56.

A J Culyer, J. Wiseman, M. F. Drummond, P. A.

West. "What accounts for the higher costs of teaching hospitals?" Social and Economic Administration,

1978, 12: 20-30.

57.

A J Culyer. "Economics and the health

services: missionary role of economists", Surgical News, No. 5, Summer 1978, 2-4.

58.

A J Culyer. "Editorial", Epidemiology and Community Health, 1979,

33: .

59.

A J Culyer. Comment on Theories and

Measurement in Disability by R. G. A. Williams, Epidemiology and Community Health, 1979, 33: .

60.

A J Culyer. "Into the valley: review

article of 'Charge' by A. Seldon", Social Policy

and Administration, 1979, 13: 65-68.

61.

A J Culyer. "What do health services do

for people?" Search, 1979, 10: 262-268.

62.

A J Culyer, J Wiseman. "Frameworks for

evaluating economic effects of budget and financial transfers in the EEC",

in Study Group on the Economic Effects of

Budget and Financial Transfers in the Community, Part II, Brussels,

Commission of the European Communities, 1979.

63.

A J Culyer. "Cost-sharing: financial

aspects and policies", in B. Abel-Smith (ed.), Sharing Health Care Costs, Washington D.C.:

National Center for Health Services Research;

U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1980, 18-19.

64.

A J Culyer. "Economics and the health

services", in R. M. Grant and G. K. Shaw (eds.), Current Issues in Economic Policy, 2nd ed., London: Philip Allan,

1980, 164-186.

65.

A J Culyer, A K Maynard. Treating ulcers with Cimetidine can be more cost-effective than surgery", Medeconomics,

1980 1: 12-14.

66.

A J Culyer. "Externality models and

health: a Rückblick over the last twenty years",

in P. M. Tatchell (ed.), Economics and Health: Proceedings of the First Australian Conference of

Health Economists, Canberra: Australian National

University Press, 1980, 139-157. (reprinted with changes in The Economic Record, 1980, 56:

222-30).

67.

A J Culyer. Discussion of Universality and

Selectivity in the Targeting of Government Health/Welfare Programs by D. Dixon in P. M. Tatchell (ed.), Economics and Health: Proceedings of the

First Australian Conference of Health Economists, Canberra, Australian National

University Press, 1980,

11-17.

68.

A J Culyer, Heather Simpson. "Externality

models and health: a Rückblick over the last twenty

years", The Economic Record,

September 1980, 56: 222-30. (Reprint with changes in P. M. Tatchell

ed., Economics and Health: Proceedings of

the First Australian Conference of Health Economists, Canberra: Australian

National University Press, 1980, 139-157).

69.

A J Culyer, M. Pfaff, H. Hauser. "Report on financial aspects and policies"

in A. Brandt, B. Horisberger and W. P. von Wartburg

(eds.), Cost-Sharing in Health Care, Heidelberg: Springer,

1980.

70.

A J Culyer, A K Maynard.

"Cost-effectiveness of duodenal ulcer treatment", Social Science and Medicine, 15C, 3-11,

1981. (Reprinted in shortened form in Bernard S. Bloom (ed.), Cost-Benefit and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

in Policymaking. Cimetidine as a Model, New York: Biomedical

Information Corporation, 1982, 128-31).

71.

A J Culyer. "The IEA's unorthodoxy",

in R. Harris and A. Seldon (eds.), The Emerging Consensus

...? London:

Institute of Economic Affairs, 1981, 99-119.

72.

A J Culyer. "Acht Trugschlüsse über das britische

Gesundheitswesen", Medita, 1981,

6: 22-27.

73.

A J Culyer. "European workshop on health

indicators: a draft report", Revista Internacional de Sociologi,

1981, 39: 151-171.

74.

A J Culyer. "Economics, social policy and

social administration: the interplay between topics and disciplines", Journal of Social Policy, 1981, 10: 311-29.

75.

A J Culyer. "Health, economics and health economists"

in J. Van de Gaag and M. PerIman

(eds.), Health Economics and Health

Economists, Amsterdam:

North-Holland, 1981.

76.

A J Culyer. "Economics, health and health

services" in R. Clara et al, Health

and Economy, Part 1, Antwerp: Antwerp University Press, 1981, 19-33.

77.

A J Culyer, A K Maynard.

"Cost-effectiveness of duodenal ulcer treatment", in Bernard S. Bloom

(ed.) Cost-Benefit and Cost-Effectiveness

Analysis in Policymaking: Cimetidine as a Model, New York: Biomedical

Information Corporation, 1, 128-13. (Reprint of 1981 Social Science and Medicine article).

78.

A J Culyer, A K Maynard, A

H Williams. "Alternative systems of health care provision: an essay on

motes and beams" in Mancur Olson (ed.), A New Approach to the Economics of Health

Care, Washington:

American Enterprise Institute, 1982, 131-150.

79.

A J Culyer, J Wiseman, M F Drummond, P A West.

"Revenue allocation by regression: a rejoinder", Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 1982, 145: Part 1, 127-33.

80.

A J Culyer. "Health services in the mixed

economy" in Lord Roll of Ipsden (ed.), The Mixed Economy, London, Macmillan,

1982, 128-144. (reprinted in Magyar as "Egeszsegugyi szolgaltatasok a vegyes gazdasagban", Esely, 9113,

1991, 37-48).

81.

A J Culyer. "Egeszsegugyi

szolgaltatasok a vegyes gazdasagban", Esely, 9113, 1991, 37-48).

82.

T

Sandler, A J Culyer. "Joint

products and multi-jurisdictional spillovers", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1982, 97: 707-716.

83.

A J Culyer. "Assessing

cost-effectiveness", in H. D. Banta (ed.), Resources for Health: Technology Assessment for Policy Making, Westport: Praeger, 1982, 107-120.

84.

A J Culyer. "The NHS and the market:

images and realities", in G. McLachlan and A. Maynard (eds.), The Public/Private Mix for Health: the

Relevance and Effects of Change, London, Nuffield Provincial Hospitals

Trust, 1982, 25-55.

85.

A J Culyer. "Health care and the market: a

British lament, Journal

of Health Economics, 1982, 1: 299-303.

86.

T

Sandler, A J Culyer. Joint products

and multi-jurisdictional spillovers: some public goods geometry", Kyklos, 1982, 35: 702-9.

87.

A J Culyer. "A Hatekonysag

Keresese a Kozuleti Szektorban: Kozgadzak contra dr. Pangloss" (trs. from English by Otto Gado), Penziigyi Szemle, 27,

1983, 378-384.

88.

A J Culyer. "Introduction" to Health

Indicators, ed. A. J. Culyer, London,

Martin Robertson, 1983, 1-22.

89.

A J Culyer. "Conclusions and

recommendations" in A. J. Culyer (Ed.) Health

Indicators, London:

Martin Robertson, 1983, 186-193.

90.

A J Culyer. "Effectiveness and efficiency

of health services", Effective

Health Care, 1983, 1: 7-9.

91.

A J Culyer, J. MacFie,

A. Wagstaff. "Cost-effectiveness of foam elastomer

and gauze dressings in the management of open perineal

wounds", Social Science and Medicine,

1983, 17: 1047-53.

92.

A J Culyer. "Public or private health

services: a skeptic's view", Journal

of Policy Analysis and Management, 1983, 2: 386-402.

93.

A J Culyer. "The marginal approach to

saving lives", Economic Review,

1, 1983, 21-23.

94.

A J Culyer. "Economics without economic

man?" Social Policy and

Administration, 1983, 17: 188-203.

95.

A J Culyer, B Horisberger.

"Medical and economic evaluation: a postscript" in A. J. Culyer and

B. Horisberger (eds.), Economic and Medical Evaluation of Health Care Technologies, Heidelberg: Springer,

1983, 347-358. (Also published separately by the same publishers in German).

96.

A J Culyer. "La contribución del Análisis

Económico a la Pólitica Social ", in J-J. Artells (ed.), Primeres Jornades dEconomia dels Serveis

Socials, Barcelona, Impres Layetana, 1983, 17-34.

97.

A J Culyer. "Marco para la evaluación

multidisciplinaria de los servicios sociales", in J-J. Artells (ed.), Primeres Jornades dEconomia dels

Serveis Socials, Barcelona, Impres Layetana, 1983, 35-39.

98.

A J Culyer, A

Wagstaff, J MacFie. "Foam elastomer

and gauze dressings in the management of open perineal

wounds: a cost-effectiveness study", British

Journal of Clinical Practice, 1984, 38:

263-8.

99.

A J Culyer, J Posnett.

"Profit regulation in the drug industry: a bitter pill?",

Economic Review, 1984, 2:

19-21.

100.

A J Culyer. "The quest for efficiency in

the public sector: Economists versus Dr. Pangloss (or

why conservative economists are not nearly conservative enough)", in H. Hanusch (ed.), Public

Finance and the Quest for Efficiency, Proceedings of the 38th Congress of

the UPF, Copenhagen, Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1984, 39-48.

101.

A J Culyer, J Posnett.

"Would you choose the Welfare State?" Economic Affairs, 1985, 5: 40-42.

102.

A J Culyer. "What's wrong with economics

textbooks?",

Economics, 1985, 21: 15-17.

103.

A J Culyer. "A health economist on medical

sociology: reflections by an unreconstructed reductionist, Social Science and Medicine, 1985, 20: 1013-21.

104.

A J Culyer. "On being right or wrong about

the welfare state", in P. Bean, J. Ferris and D. Whynes

(eds.), In Defence

of Welfare, London:

Tavistock, 1985, 122-41.

105.

A J Culyer. "Discussion" in N. Wells

(ed.), Pharmaceuticals among the Sunrise Industries, London: Croom Helm,

1985, 218-224.

106.

A J Culyer, S Birch. "Caring for the

elderly: a European perspective on today and tomorrow", Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law,

1985, 10: 469-87.

107.

A J Culyer. "What dangers from medical

monopoly?" Economic Affairs,

1986, 6: 56-7.

108.

A J Culyer. "The scope and limits of

health economics (with reference to economic appraisals of health

services)" in Oekonomie des Gesundheitswesen,

Jahrestagung des Vereins für Socialpolitik, Gesellschaft für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften,

Neue Folge Band 159, 1987,

Berlin: Duncker & Humblot,

31-53.

109.

A J Culyer. "The future of health

economics in the U.K.

", in Health Economics: Prospects

for the Future, ed. G. Teeling Smith, London: Croom Helm, 1987, 15-32.

110.

A J Culyer. "Assessing the costs and

benefits of pharmaceutical research", in G. Teeling

Smith (ed.), Costs and Benefits of

Pharmaceutical Research, London:

Office of Health Economics, 1987, 25-27.

111.

A J Culyer, C Blades, A

Walker.

"Health service efficiency, appraising the appraisers - a critical review

of economic appraisal in practice", Social

Science and Medicine, 1987, 25,

461-72.

112.

A J Culyer. "Technology assessment in

Europe: its present and future roles", in E E H.

Rutten and S. J. Reiser

(eds.), The Economics of Medical

Technology, Berlin:

Springer, 1987, 54-79.

113.

A J Culyer. "Health economics: the topic

and the discipline", in J. M. Horne (ed.), Proceedings of the Third Canadian Conference on Health Economics, 1986,

Winnipeg: Department of Social and Preventive

Medicine, University of Manitoba,

1987, 1-18.

114.

A J Culyer. "Discussion of R. G. Evans et

al, Toward efficient aging: rhetoric and

evidence", in J. M. Horne (ed.), Proceedings

of the Third Canadian Conference on Health Economics, 1986, Winnipeg: Department of Social and Preventive Medicine,

University of Manitoba,

1987, 170-1.

115.

A J Culyer. "Inequality of health services

is, in general, desirable", in D. Green (ed.), Acceptable Inequalities? Institute of Economic Affairs, London: 1988, 31-47.

116.

A J Culyer. "The radical reforms the NHS needs

- and doesn't", Minutes of Evidence

Taken before the Social Services Committee, London: HMSO, 1988, 238-242.

117.

A J Culyer. Comments on Public

Hospital Performance Assessment by

Arthur Andersen and Co., in Response From the Hospital Boards' Association of New Zealand to "Unshackling the Hospitals

the Report of the Hospital and Related Services Taskforce, Hospital Boards'

Association, New Zealand,

1988.

118.

A J Culyer. "Medical care and the

economics of giving", in M. Ricketts (ed.) Neoclassical Microeconomics, vol. 2, Aldershot: Edward

Elgar, 1988, 310-318 (reprint of 1971 article in Economica).

119.

A J Culyer. "The normative economics of

health care finance and provision", Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 5, 1, 1989,

34-58. (reprinted with changes in A. McGuire, P. Fenn and K. Mayhew (eds.) Providing Health Care: The Economics of

Alternative Systems of Finance and Delivery, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991, 65-98,

also in A J Culyer (Ed.) Health

Economics: Critical Perspectives on the World Economy, London: Routledge,

2006, 148-157)

120.

A J Culyer. "Commodities, characteristics

of commodities, characteristics of people, utilities and the quality of

life", in S. Baldwin, C. Godfrey and C. Propper (eds.), The

Quality of Life: Perspectives and Policies. London: Routledge,

1989, 9-27. (Reprinted 1994)

121.

A J Culyer. "The economics of health

systems", in R. G. Butler and D. P. Doessel

(eds.) Health Economics: Australian

Readings, Sydney: Australian Professional Publications, 1989, 145-166

(reprint of 1969 article in The Price of Health).

122.

A J Culyer. "Implications of the

Ministerial Review of the NHS", in Opportunities

for the Independent Sector: Articles from the NHS Review, Annual Conference

Review, Independent Hospitals Association, 1989, 6-9.

123.

A J Culyer. "A glossary of the more common

terms encountered in health economics", in M. S. Hersh-Cochran

and K. P. Cochran (eds.), Compendium of

English Language Course Syllabi and Textbooks in Health Economics,

Copenhagen: WHO, 1989, 215-234.

124.

A J Culyer. "Cost containment in Europe", Health

Care Financing Review, Annual Supplement, 1989, 21-32. (reprinted

in Health Care Systems in Transition,

Paris: OECD, 1990.)

125.

A J Culyer. "Competition and markets in

health care: what we know and what we don't, Part I", Cardiology Management, 1990, 3: 15-18.

126.

A J Culyer. "Competition and markets in

health care: what we know and what we don't, Part II ", Cardiology

Management, 1990, 3: 36-38.

127.

A J Culyer. "Cost containment in Europe", in Health

Care Systems in Transition, Paris: OECD, 1990, 000-000. (Reprint of 1989

article in Health Care Financing Review ).

128.

A J Culyer, B Luce, A

Elixhauser. "Socioeconomic evaluations: an

executive summary ", in Culyer (ed.), Standards

for Socioeconomic Evaluation of Health Care Products and Services, Berlin:

Springer, 1990, 1-12.

129.

A J Culyer, J W Posnett.

"Hospital behaviour and competition", in A. J. Culyer, A. K. Maynard

and J. W. Posnett (eds.), Competition in Health Care: Reforming the NHS, London: Macmillan,

1990, 12-47.

130.

A J Culyer , A K Maynard, J W Posnett. "Reforming health care: an

introduction to the economic issues", in A. J. Culyer, A. K. Maynard and

J. W. Posnett (eds.) Competition in Health Care: Reforming the NHS, London: Macmillan,

1990, 1-11.

131.

A J Culyer. "Funding the future", in The White Paper and Beyond: One Year On,

(eds. E. J. Beck and S. A. Adam), Oxford: Oxford University Press

(Oxford Medical Publications), 1990, 58-69.

132.

A J Culyer. "Incentivos: para qué? Para quién?

De qué tipo?", in Associatión de Economia de la Salud, Reforma Sanitaria e Incentivos, Assoc.

de Econ. de la Salud, Barcelona, 1990, 39-53.

133.

A J Culyer. "The promise of a reformed

NHS: an economists angle", British

Medical Journal, 302, 1991,

1253-1256. (reprinted

in Professional Judgment and Decision

Making, Offprints (4), Milton

Keynes, Open University Press, 1992, 19-22).

134.

A J Culyer. "The normative economics of

health care finance and provision", in A. McGuire, P. Fenn and K. Mayhew

(eds.) Providing Health Care: the Economics

of Alternative Systems of Finance and Delivery, Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1991, 65-98 (reprint with changes of 1989 article in Oxford

Review of Economic Policy).

135.

A J Culyer. "Conflicts between equity

concepts and efficiency in health: a diagrammatic approach", Osaka Economic Papers, 1991, 40: 141-154. (Reprinted in A. M. El-Agraa

(ed.) Public and International Economics,

New York: St Martins Press, 42-58).

136.

A J Culyer. "Egéazségügyi

szolgáltatások a vegyes gazdaságban", Esély, 91/3,

1991, 37-48 (reprint in Magyar of Health services in the mixed economy, in The Mixed Economy, 1982).

137.

A J Culyer. "Incentives: for what? For whom?

What Kind?", in G. Lopez-Casasnovas (ed.), Incentives in Health Systems, Berlin: Springer, 1991,

15-23 (reprint in English of article in Spanish in Reforma

Sanitaria e Incentivos, 1990),

138.

A J Culyer. "Reforming health services:

frameworks for the Swedish review", in A. J. Culyer (ed.) International Review of the Swedish Health

Care System, Studiefoerbundet Naeringsliv

och Saemhalle (Center for

Business and Policy Studies), Stockholm, 1991, 1-49.

139.

A J Culyer. "The promise of a reformed

NHS: an economists angle", in J. Dowie

(compiler) Professional Judgment and

Decision Making, Offprints (4), Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1992,

19-22 (reprint of 1991 article in British Medical Journal).

140.

A J Culyer. "Hospital competition in the

UK: a (possibly) useful framework for the future" in R. B. Deber and G. G. Thompson (eds.), Restructuring Canadas Health Services System: How Do We Get There From

Here?, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992, 317-330.

141.

A J Culyer. "The morality of efficiency in

health care - some uncomfortable implications", Health Economics, 1,

1992, 7-18. (Reprinted in A. King, T. Hyclak, S. McMahaon and R.

Thornton (eds.), North American Health

Care Policy in the 1990s, Chichester: Wiley,

1993, 1-24).

142.

A J Culyer, E van Doorslaer,

A Wagstaff. "Utilisation as a measure of equity

by Mooney, Hall, Donaldson and Gerard: Comment, Journal of Health Economics,

1992, 11: 93-98.

143.

A J Culyer. Need, greed and Mark Twain's cat,

in A. Corden, E. Robertson and K. Tolley

(eds.) Meeting Needs in an Affluent

Society, Aldershot: Avebury,

1992, 31-41.

144.

A J Culyer. "Sjukvård och sjukvårdsfinansiering

i Sverige" ("Health

care and health care financing in Sweden"), in A. J. Culyer et

al. Svensk Sjukyvård - Bäst i Världen? (Swedish Health Care -

the Best in the World?), Stockholm:

SNS Förlag, 1992, 9-31.

145.

A J Culyer. "Att

reformera sjukvärden:

ramar för den svenska genomgången"

("Reforming health services: Frameworks for the Swedish Review"), in

A. J. Culyer et al. Svensk Sjukyår

- Bäst i Världen? (Swedish

Health Care - the Best in the World?),

Stockholm: SNS Förlag, 1992, 32-65.

146.

A J Culyer. "Evaluation des technologies médicales: progrés des techniques et progrès de la science

économique", in J-R Moatti and C. Mawas (eds.), Evaluation des Innovations Technologiques et

Décisions en Santé Publiques, Paris: Coll. Analyse et Prospective, Eds

INSERM, 1992, 37-47.

147.

A J Culyer (with 34 others). The Appleton International

Conference: developing guidelines for decisions to forgo life-prolonging

medical treatment, Journal of Medical

Ethics, 1992, 18 (Supplement):

3.

148.

A J Culyer, E van Doorslaer,

A Wagstaff. "Access, utilisation and equity: a further comment, Journal of Health Economics,

1992, 11: 207-210.

149.

A J Culyer. "Health, health expenditures,

and equity", in E. van Doorslaer, A. Wagstaff

and F. Rutten (eds.) Equity in the Finance and Delivery of Health Care: an International

Perspective, Oxford: Oxford University Press (Oxford Medical Publications),

1993, 299-319,

150.

A J Culyer, A Meads.

"The United Kingdom:

effective, efficient, equitable?" Journal

of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 1993, 17: 667-688.

151.

A J Culyer. "Health care insurance and

provision", in N. Barr and D. Whynes (eds.) Current

Issues in the Economics of Welfare, Houndmills:

Macmillan, 1993, 153-175.

152.

A J Culyer. "The morality of efficiency in

health: some uncomfortable implications", in A. King, T. Hyclak, S. McMahon and R. Thornton (eds.) North American Health Care Policy in the

1990s, Chichester: Wiley, 1993, 1-24 (reprinted

from Health Economics, 1992).

153.

A J Culyer, A

Wagstaff. "QALYs versus HYEs", Journal of Health Economics,

1993, 12: 311-323.

154.

A J Culyer. "Conflicts between equity

concepts and efficiency in health: a diagrammatic approach", in A. M. El-Agraa (ed.) Public

and International Economics, New York, St Martin's Press, 1993, 42-58

(reprinted from Osaka Economic Papers,

1991).

155.

A J Culyer. "EI mercado interior: un medio

aceptable para conseguir un fin deseable", Hacienda Pública Española, 1993, 126: 39-49.

156.

A J Culyer, A

Wagstaff. "Equity and equality in

health and health care", Journal of Health Economics, 1993, 12:

431-457 (reprinted in N Barr (ed.) Economic

Theory and the Welfare State, Cheltenham: Edward

Elgar, 2001, 231-257 and in A J Culyer (Ed.) Health Economics: Critical Perspectives on

the World Economy, London:

Routledge, 2006, 483-509).

157.

A J Culyer, B Horisberger,

B Jonsson, F F F M Rutten.

"Introduction", European

Journal of Cancer, 1993, 29A, Suppl 7, S1-S2.

158.

A J Culyer, B. Jonsson.

"Ought cancer treatments to be immune from socio-economic evaluation? An

epilogue", European Journal of

Cancer, 1993, 29A, Supplement 7,

S31-S32.

159.

A J Culyer. "NHS reforms: a challenge or a

threat to NHS values?" The Health

Business Summary, No. 11, October 1994, 3-4.

160.

A J Culyer. "Finding answers to simple

questions", Parliamentary Brief,

1994, 3: 64.

161.

A J Culyer. "A proposal for a checklist of

reputable economics journals for the UK profession", Royal Economic Society Newsletter, 87, 1994, 16-17.

162.

A J Culyer. "The Culyer report (letter), The Lancet, 344, December 24/31, 1994, 1774.

163.

A J Culyer. "Economics and the incomplete

case for public support for research" (letter), Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 29,

January/February 1995, 72.

164.

A J Culyer. "Cure at a cost", Times Higher Education Supplement,

(supplement, Synthesis: Medicine), January 20, 1995, i.

165.

A J Culyer. "Need: the idea won't do - but

we still need it", (Editorial) Social

Science and Medicine, 1995, 40:

727-730.

166.

A J Culyer. "Supporting research and

development in the NHS - Key points from the Culyer Report ", Refocus, 1995, Winter:

4-5.

167.

A J Culyer. "Supporting research and

development in the National Health Service", Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 1995, 29: 216-224.

168.

A J Culyer. "Supporting R&D in the NHS

- some unresolved issues" in House of Lords, Minutes of Evidence Taken Before the Select Committee on Science and

Technology, HL Paper 12-iv, London: HMSO, 1995, 168-176.

169.

A J Culyer. Evidence before House of Lords

Select Committee on Science & Technology, Minutes of Evidence Taken before the Select Committee on Science and

Technology, HL Paper 12-iv, London: HMSO, 1995, 183-195 (passim)

170.

A J Culyer, A

Wagstaff. "QALYs versus HYEs: A

reply to Gafni, Birch and Mehrez",

Journal of

Health Economics, 1995, 14: 39-45.

171.

A J Culyer. "Preface: all is a flux yet

all is the same!", in International

Developments in Health Care, ed. Roger Williams, London, Royal College of

Physicians, 1995, vii-x.

172.

A J Culyer. "Chisels or screwdrivers? A

critique of the NERA proposals for the reform of the NHS", in A. Towse

(ed.) Financing Health Care in the UK: A

Discussion of NERA's Prototype Model to Replace the NHS, London: Office of

Health Economics, 1995, 23-37.

173.

A J Culyer. "Taking advantage of the new

environment for research and development" in M. Baker and S. Kirk (eds.) Research and Development for the NHS:

Evidence. Evaluation and Effectiveness, Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1995, 37-49

(reprinted with changes in Baker and Kirk 1998).

174.

A J Culyer. "Fundamentals for promoting

health gain efficiently and equitably in Northern Ireland: some reactions to

the Consultation Document Regional Strategy for Health and Social W11being,

1997-2002", in Northern Ireland Economic Council, Health and Personal Social Services to the Millennium, Belfast,

NIEC, 1995, 45-65.

175.

A J Culyer. "The NHS reforms - a challenge

or a threat to NHS values?" in A. J. Culyer and Adam Wagstaff (eds.) Reforming Health Care Systems: Experiments

with the NHS, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1996, 1-14.

176.

A J Culyer, R G Evans. "Mark Pauly on welfare

economics: normative rabbits from positive hats", Journal of Health Economics,

1996, 15: 243-251 (reprinted in A J

Culyer (Ed.) Health Economics: Critical

Perspectives on the World Economy, London:

Routledge, 2006, 148-157).

177.

A J Culyer. "A personal perspective on

progress in research and development", in K. Aspinall

(ed.) The York Symposium on Health,

University of York, York, 1996, 33-44.

178.

A J Culyer. "The principal objective of

the NHS ought to be to maximise the aggregate

improvement in the health status of the whole community", British Medical Journal, 314, 667-669, 1997. (Reprinted with

changes in B. New (ed.), Rationing: Talk

and Action, London:

Kings Fund and BMJ, 1997, 95-100.

179.

A J Culyer. "0 impacta da economia da

saude nas politicas publicas", Nota

Economicas, 1997, 7: 38-48.

180.

A J Culyer. "Maximising

the health of the whole community: the case for", in B. New (ed.), Rationing: Talk and Action, London: Kings Fund and

BMJ, 1997, 95-100. (reprint with changes of BMJ 1997

article).

181.

A J Culyer. "A rejoinder to John

Harris", in B. New (ed.), Rationing:

Talk and Action, London:

Kings Fund and BMJ, 1997, 106-107.

182.

A J Culyer. Altruism and economics, in A. Nordgren and C-G. Westrim (eds.),

Altruism, Society, Health Care, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Uppsala,

1998, 51-66.

183.

A J Culyer. Health and welfare resources at

the University of

York, Health-Care Focus, February 1998, 13-14.

184.

A J Culyer. Need - is a consensus possible? Journal of Medical Ethics, 1998, 24: 77-80 (Guest Editorial).

185.

A J Culyer. Foreword, in M. Baker and S. Kirk

(eds.) Research and Development for the

NHS, Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998, vi-x.

186.

A J Culyer. Taking advantage of the new

environment for research and development in Baker and Kirk (eds.), Research and Development for the NHS,

Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998, 53-66.

(reprint with changes of 1996 edition).

187.

A J Culyer. How could anyone imagine R&Ds

trial test is better patient care?, Health Services Journal, 9 April 1998, 18 (letter).

188.

A J Culyer. The NHS - an assessment, in L

Mackay, K Soothill and K Melia

(eds.), Classic Texts in Health Care,

Oxford, Butterworth Heinemann, 1998,

316-321 (Reprint of chapter 11 from Need

and the National Health Service, 1976).

189.

A J Culyer. How ought health economists to

treat value judgments in their analyses?, in M L Barer, T E Getzen and G L Stoddart (eds) Health, Health

Care and Health Economics, Chichester, Wiley,

1998, 363-371.

190.

A J Culyer. An input-outcome paradigm for NHS

research in forensic mental health, Criminal

Behaviour and Mental Health, 1999, 9:

355-371.

191.

A J Culyer. Economics and public policy: research and development as a public good in

P C Smith (ed.) Reforming Markets in

Health Care: An Economic Perspective, Buckingham,

Open University Press, 2000, 117-137.

192.

A J Culyer, A

Wagstaff. "Equity and equality in health and health care", in N Barr

(ed.) Economic Theory and the Welfare

State, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2000. (Reprinted from Journal of Health Economics,

1993, 12: 431-457.)

193.

A J Culyer. Economics and ethics in health

care (editorial), Journal of Medical

Ethics, 2001, 27: 2001: 217-222.

194.

A J Culyer. Equity - some theory and its

policy implications, Journal of Medical

Ethics, 2001, 27: 275-283.

195.

A J Culyer. Values, policy impact and the

credibility of health economists, in W R Swan and P Taylor (eds.) Forward

to Basics: Promoting Efficiency While Preserving Equity (Proceedings of the

7th Canadian Conference on Health Economics, CHERA/ACRES, Carleton University,

Ottawa, 2001, 37-47.

196.

A J Culyer. Introduction: Ought NICE to have a