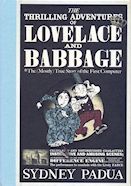

Add Lovelace, daughter of Lord Byron: mathematician, gambler and proto-programmer, whose writings contained the first ever appearance of general computing theory, a hundred years before an actual computer was built. And Charles Babbage, eccentric inventor of the DIFFERENCE ENGINE, an enormous clockwork calculating machine that would have been the first computer, if he had ever finished it. But what if things had been different?

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage presents a delightful alternative reality in which Lovelace and Babbage do build the DIFFERENCE ENGINE and use it to create runaway economic models, battle the scourge of spelling errors, explore the wider realms of mathematics and, of course, fight crime – for the sake of both London and science. Extremely funny and utterly unusual, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage comes complete with historical curiosities, extensive footnotes and never-before-seen diagrams of Babbage’s mechanical, steam-powered computer. And ray guns.

The tale of a Pocket Universe in which Lovelace and Babbage live to complete the Analytical Engine, and use it to have thrilling adventures and fight crime (the crimes of street music and poetry, that is).

This starts off as a relatively straightforward account of Charles Babbage, Ada Lovelace,

and the never-to-be-completed Analytical Engine, the famous programmable mechanical computer,

told in lovely graphic novel format.

But that real life story ends unhappily, and too soon

(Lovelace died at the age of 36, and Babbage never completed his masterpiece).

This starts off as a relatively straightforward account of Charles Babbage, Ada Lovelace,

and the never-to-be-completed Analytical Engine, the famous programmable mechanical computer,

told in lovely graphic novel format.

But that real life story ends unhappily, and too soon

(Lovelace died at the age of 36, and Babbage never completed his masterpiece).

Rather than the book stopping at page 40, the fictional story begins, in an alternate universe, where the laws of time are a little more fluid, the engine is completed, and the super-geniuses Babbage and Lovelace, agents of The Crown, team up to fight crime, meet Wellington and Brunel, banter about computers, and have thrilling steampunk adventures, all gloriously illustrated, and copiously footnoted.

Those footnotes are there to point out the links (sometimes tenuous, often not) between what is happening in the tales, and what happened in reality. There is a lot of research behind these brief tales, with some footnotes having endnotes of their own, with more copious material; and some of those endnotes have further footnotes of their own. These tell of the (real life) events behind the (sadly so very fictional) scenes being illustrated.

Sometimes a page of research is captured by a quick joke, or a single panel. But one whole story depends on it: the visitor who distracts Coleridge when writing Kubla Khan is none other than that destroyer of poetry, Lovelace herself! The evidence is convincingly presented; only one tiny detail argues against it, scrupulously recorded by the author: “Some may object that she was born eighteen years after the composition of the poem, but this anomoly is easily explained”.

Overall, this is a delight, especially if you are interested in the Analytical Engine, and the history behind it. The individual stories probably do not stand on their own, but when supported by triply-nested footnotes, and superb illustrations, everything comes together brilliantly.