Acute Physical Health Shocks and Mental Health Care

Wei Song

Supervisors: Panos Kasteridis, Rowena Jacobs

Health Econometrics and Data Group

2nd October, 2024

[1.0] Background and motivation

-

Physical and mental health are closely related with biological and behavioural pathways.

30% of people with LTCs have mental health problems;

46% of people with mental health problems have LTCs.

(Naylor et al., 2012) - More research focuses on how mental health impacts physical health. Reciprocal pathways and endogeneity bring about challenges in modelling impact.

[1.1] Acute phyiscal health shock

- Acute myocardio infarction, cerebral infarction, and new diagnosis of cancer

- Unanticipated timing helps with the endogeneity problem

- The experience of an acute physical health shock are shown to negatively impact risk for depression and general anxiety disorder.

- Would acute physical health shock impact mental health service utilisation? If so, would it be increased or decreased?

[1.2] Research question

- How does the experience of acute physical health shocks impact the utilisation of specialised mental health care?

- ... for individuals who are existing specialised mental health care users

- How to capture acute physical health shock?

- How to deal with different timing for treatment and outcome measures?

- Would variations in shock intensity complicate measurement, as individuals are displaced due to hospitalisation for shock related physical care?

Possible challenges

[2.0] Data and methods

- Hospital Episode Statistics (HES): Admitted Patient Care (APC)

- Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS)

- Population: users of specialised mental health care in 2017/18

- Treatment: first experience of heart attack, shock, or first diagnosis of cancer

- Outcome: days spent in mental health care

[2.1] Mental health care pathways in England

- Primary care: GP referrals, IAPT (talking therapies)

- Community care

- Hospital care at NHS Mental Health Trust (secondary and tertiary)

- Specialist mental health care delivered at physical health setting (integrated care)

[2.2] Data and methods (cont.)

[2.3] Data and methods (cont.)

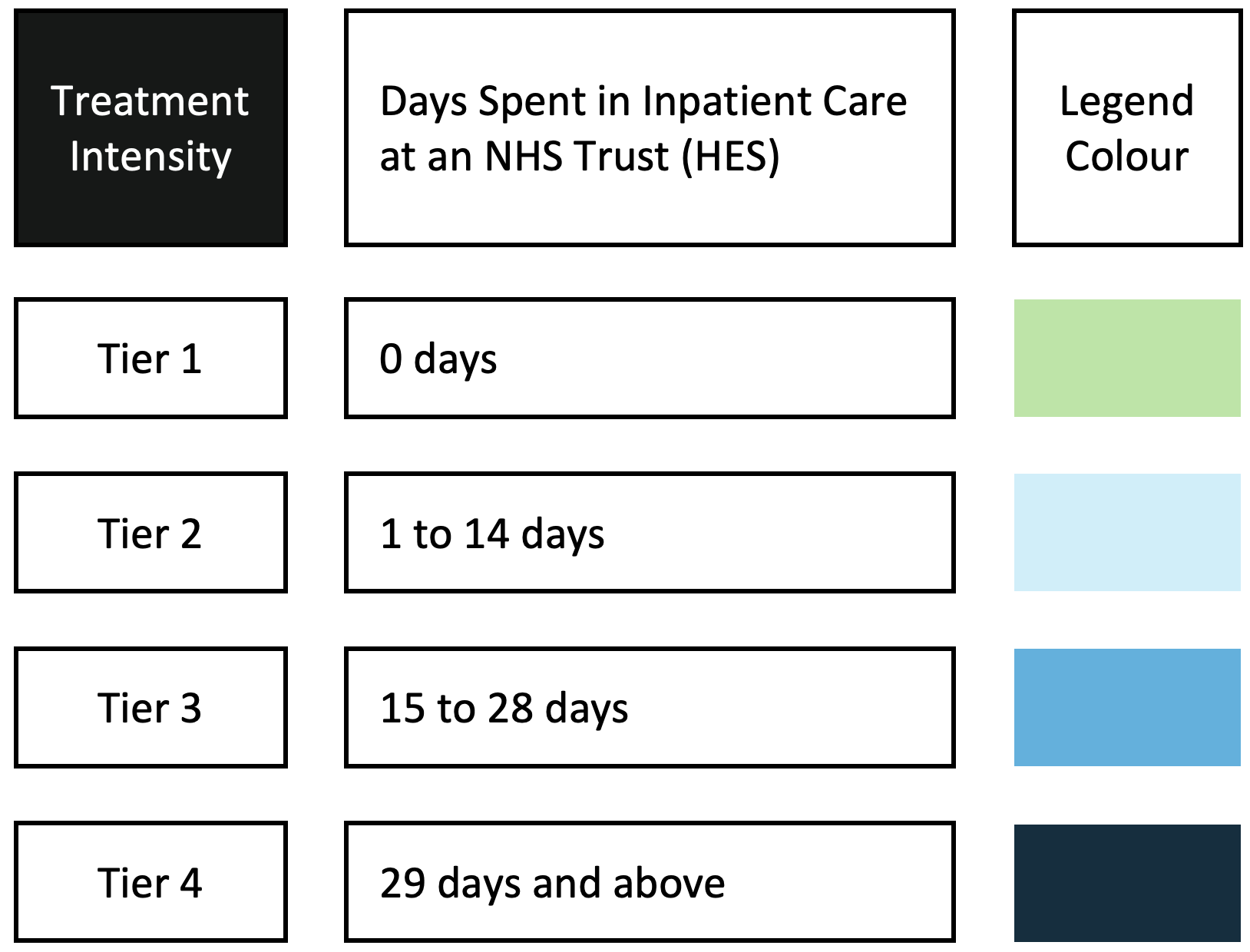

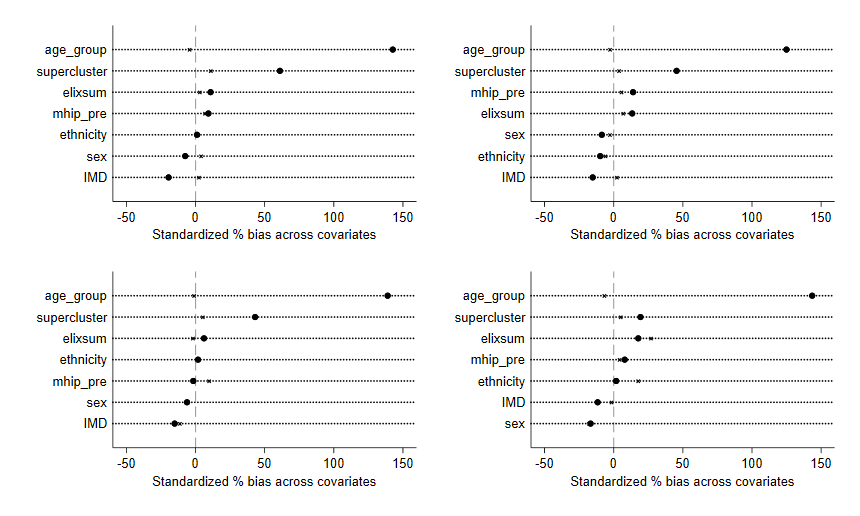

Propensity score matching

Sex Age group Mental health cluster Ethnicity IMD quartile Elixhauser comorbidity index Pre-treatment utilisation of mental health care

[3.0] Econometric setup

\( y_{it} = \alpha_0 + \alpha X_i + \beta d_i + \gamma \lambda + \color{orange}{\delta d_i \lambda} \) + \( u_{it} \)

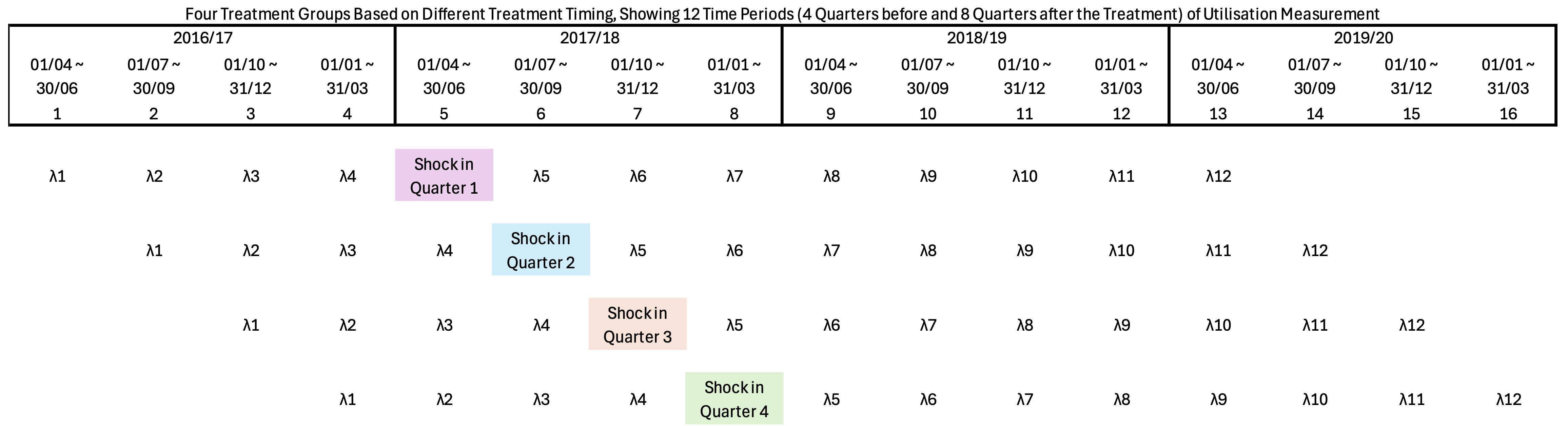

[3.1] Multi-timepoint design

Each \( \lambda \) represents a three-month period

[3.2] Stacked DiD

\( y_{it} = \alpha_0 + \alpha X_i + \beta d_i + \sum\limits_{t=2}^{T} \gamma_t \lambda_t + \sum\limits_{t=T_s}^{T} \delta_t(d_i \lambda_t) + u_{it} \)

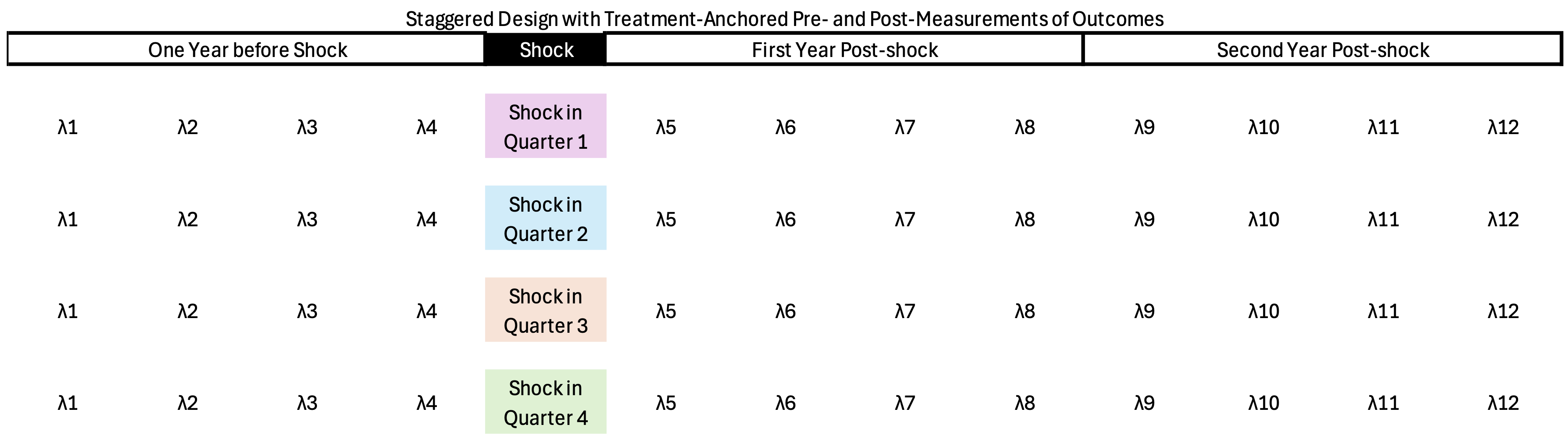

[3.3] Treatment intensity

\( \small y_{it} = \alpha_0 + \alpha X_i + \sum\limits_{k=1}^{K} \beta_k d_{ik} + \sum\limits_{t=2}^{T} \gamma_t \lambda_t + \sum\limits_{k=1}^{K} \sum\limits_{t=T_s}^{T} \delta_{tk}(d_{ik} \lambda_t) + u_{it} \)

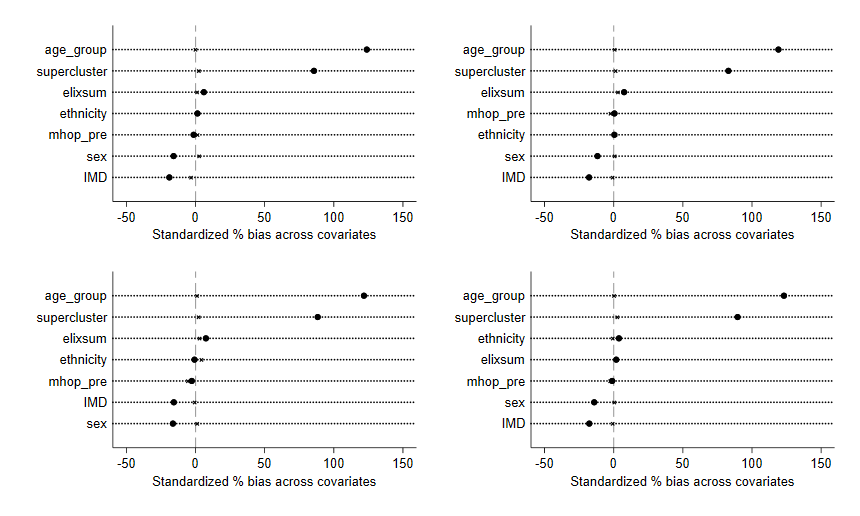

[4.0] Results for inpatient: covariate balance

[4.1] Inpatient (cont.)

- Total number of inpatient bed-days: 7.4m for 2016/17, 7.5m for 2019/20

- Average number of inpatient bed-days: 7 to 8 days per quarter

- Higher utilisation in July to December time

[4.2] Inpatient (cont.)

[4.3] Inpatient (cont.)

[4.4] Inpatient (cont.)

[4.5] Inpatient (cont.)

Men

Women

[5.0] Results for outpatient: covariate balance

[5.1] Outpatient (cont.)

- Total number of days spent in community care: 151m 2016/17, 135m 2019/20

- Average number of days range from 20 to 25 days per quarter

[5.2] Outpatient (cont.)

[5.3] Outpatient (cont.)

[5.4] Outpatient (cont.)

[5.5] Outpatient (cont.)

Men

Women

[6.0] Results, mental health care in physical setting (HES IP)

[6.1] HES IP

Men

Women

[6.2] HES OP

Men

Women

[7.0] Modelling incremental cost

- Chapter 1, survey data that links experience of PHS to increased risk for depression

- Chapter 2, admin data that links experience of PHS to altered utilisation in community and inpatient mental health care

- Chapter 3, a model that facilitates interpolation of cost difference

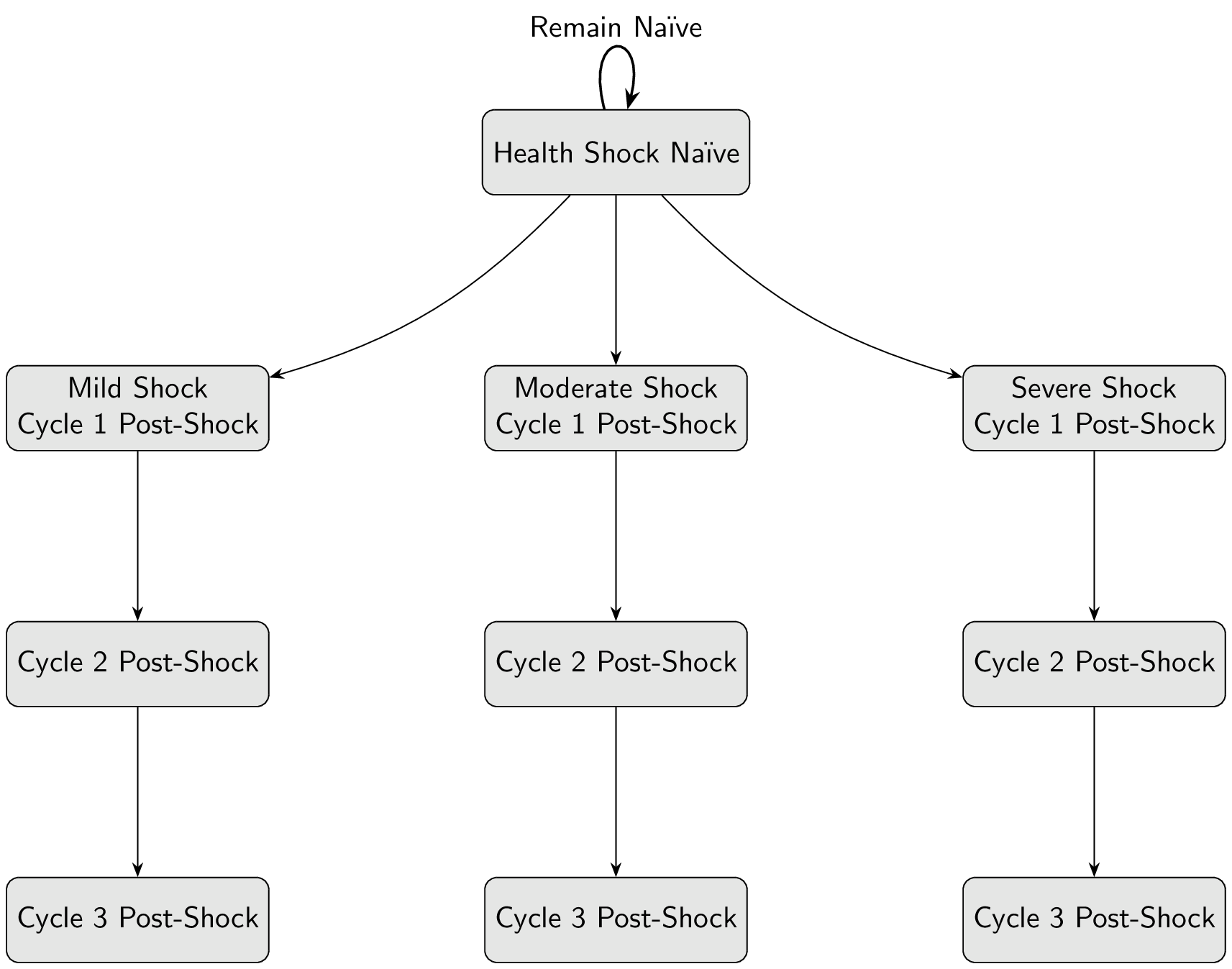

[7.1] State transition

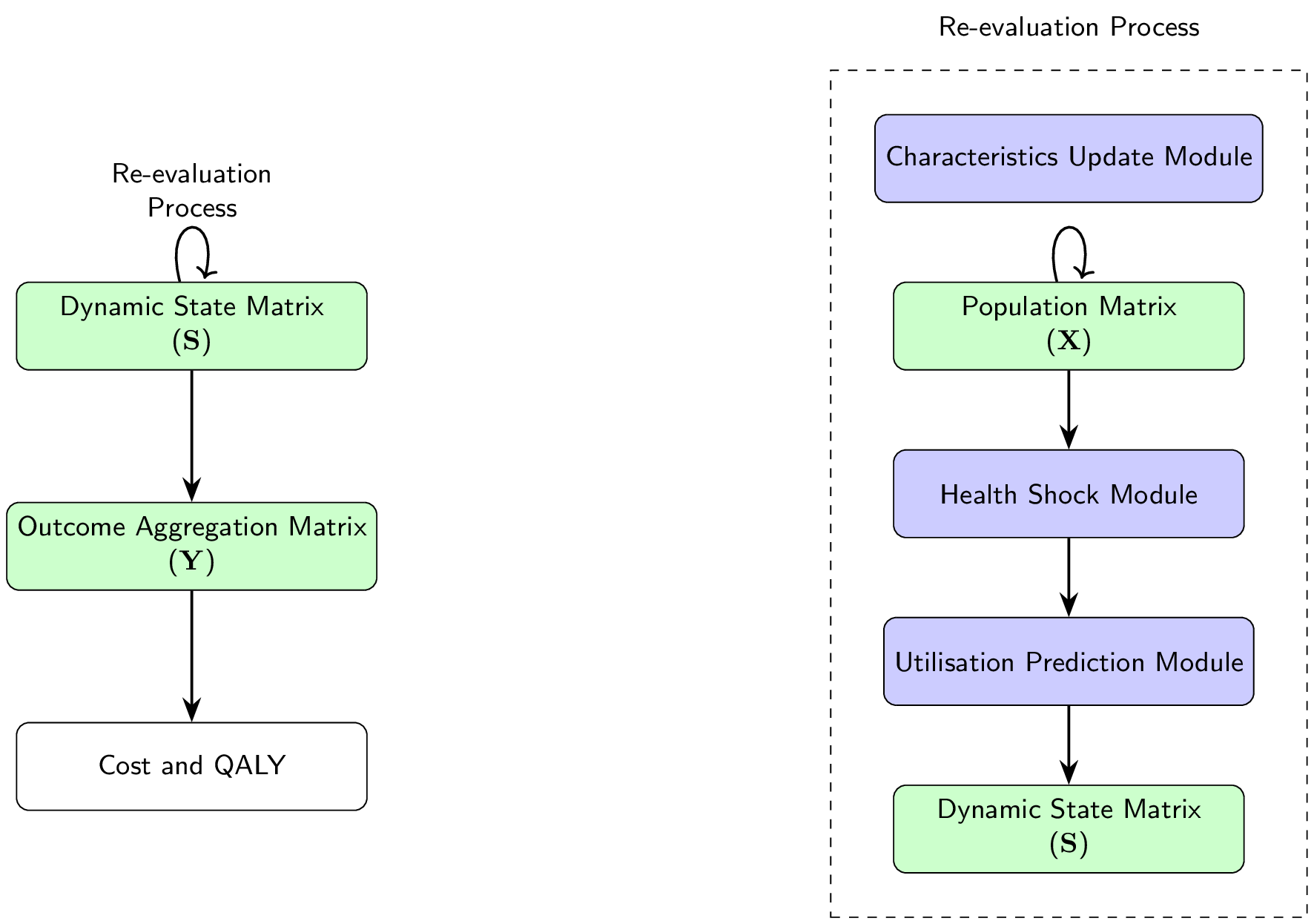

[7.2] Data structure

Population

- Age

- Gender

- Socioeconomic Status

- Comorbidity

- Care Cluster

Dynamic

State

\[

\begin{aligned}

\mathbf{S} = \{ s_{i,t}^{(l)} \mid &i = 1,\dots,N; \\

&t = 1,\dots,T; \\

&l = 1,\dots,L \}

\end{aligned}

\]

- Health shock status

- Utilisation

- QALY

Outcome

Aggregation

\[

%\mathbf{Y} =

\begin{bmatrix}

y_{1,1} & y_{1,2} & y_{1,3} \\

y_{2,1} & y_{2,2} & y_{2,3} \\

\vdots & \vdots & \vdots\\

y_{N,1} & y_{N,2} & y_{N,3}

\end{bmatrix}

\]

- Total utilisation days

- Total QALY

- Care Cluster

- Currencies: HRG & Cluster

[8.3] Model workflow

[8.0] Discussion

Displacement

Removal of utilisation during quarter of shock If present, could be picked up by TE heterogeneity of shock intensity